Introduction to Web Scraping with Python

Overview

Scraping is the process of extracting, copying, screening, or collecting data. It can be done manually or automated, using robots, spiders or crawlers. When it is automated, we usually talk about crawling. In this short introduction we use both words scraping and crawling synonymously and interchangeably. In case you would like to have more details about the differences, I recommend following blog article: Web Scraping vs Web Crawling: The Differences by Gabija Fatenaite.

Crawlers capture different kind of data:

- HTML files,

- JSON strings,

- Various binary data, such as pictures, videos, audios, …

- Web rendering files, such as CSS, JavaScript and other configuration files.

It’s important to know what files are captured by the crawler, so to save them in the right format. To extract the data we need also to analyze the code source. This require some basic understanding of HTML/CSS and the DOM tree structure.

Regarding JavaScripts, we can analyze the back-end Ajax interface, or use libraries such as Selenium and splash to simulate the implemented JavaScript rendering.

The composition of a Web Page

Web pages can be divided into three skeletons:

- HTML (Hypertext Markup Language)

- CSS (Cascading Style Sheet)

- JavaScript: for dynamic and interactive page functions

The standard form of a web page is head and body tags nested inside html tags, with the head defining the configuration and references of the page and the body defining the body of the page. According to the W3C HTML DOM standard, everything in an HTML document is a node (see w3schools):

- The entire document is a document node

- Every HTML element is an element node

- The text inside HTML elements are text nodes

- Every HTML attribute is an attribute node (deprecated)

- All comments are comment nodes

Document Object Model (DOM): allows programs and scripts to dynamically access and update the content, structure, and style of a document.

Selectors

With the HTML DOM, all nodes in the node tree can be accessed by JavaScript. New nodes can be created, and all nodes can be modified or deleted. A node can be text, comments, or elements. Usually, when we access content in the DOM, we use HTML element selectors. In order to be proficient at accessing elements in the DOM, it is necessary to have a basic knowledge of CSS selectors and syntax. This is out of scope of this article, however in the following table are some of the CSS selectors depicted:

| Selector | Example | Description |

|---|---|---|

| .class | .intro | Select all nodes with class=”intro” |

| #id | #fname | Select all nodes with id=”fname” |

| element | p | Select all p nodes |

| element,element | div,p | Select all div nodes and all p nodes |

| element element | div p | Select all p nodes inside the div node |

| element>element | div>p | Select all p nodes whose parent node is div node |

| element+element | div+p | Select all p nodes immediately after the div node |

HTTP(S) - Some Basics

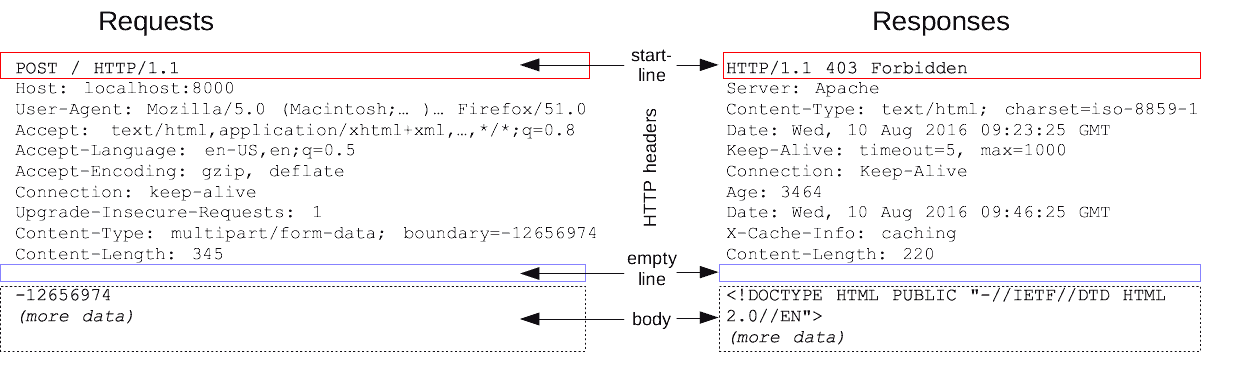

Hyper Text Transfer Protocol (HTTP) is an application protocol used to transfer hypertext data such as HTML from the web to the local browser. The communication consists of a request message from the client to the web server, followed by an HTTP response, which can be rendered by the browser. HTTP is, in fact, a rather simple networking protocol. It is text based and stateless, following a request-reply communication scheme.

HTTP Request

The request is sent from the client to the server and is organized into 4 parts: request method, request URL, request header and request body. The most commonly used request methods are POST, GET, PUT, DELETE and PATCH and are similar to the database CRUD.

The request header is used to describe additional information. Some of the more important information are Cookies and User-Agent.

It’s the request header that has to be specified when it comes to building crawlers, since the request body in the GET method is usually empty.

HTTP Response

The response is returned to the client by the server and is divided into three parts: the response status code, the response header and the response body.

The response status code indicates a successful or failed request. In case of 200, the resource data requested by the client is in the response body.

Selected status codes:

| Code | Name | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 200 | OK | The request is OK |

| 400 | Bad Request | Server unable to understand the request |

| 401 | Unauthorized | Requested content needs authentication credentials |

| 403 | Forbidden | Access is forbidden |

| 404 | Not Found | Server is unable to find the requested page |

Stateless HTTP

Stateless HTTP means that the HTTP protocol has no memory of service delivery, which means that the server does not know the client’s state. When we send a request to the server, the server processes the request and returns the corresponding response, the server is responsible for completing this process, and this process is completely independent, the server does not record the change of state before and after, that is, there is no state record.

Cookies and Sessions

Cookies are data stored on the user’s local browser by some websites for the purpose of identifying and tracking the user’s session.

The first time a browser connects with a particular server, there are no cookies.

When the server responds it includes a header that defines a cookie. Each cookie is a name-value pair. Each time the browser connects with the same server, it includes the cookie in HTTP request. The server recognize the cookie and identify the user.

Urllib vs Requests

urllib is a python stdandard library, that collects several modules for working with URLs. So it works out of the box and you don’t have to deal with package compatibility issues and has the basic modules to start scraping the web such as:

urllib.requestfor opening and reading URLsurllib.errorcontaining the exceptions raised by urllib.requesturllib.parsefor parsing URLsurllib.robotparserfor parsing robots.txt files

However, when it comes to higher level HTTP client interfaces and requests requests is recommended (by the official python docs). Indeed requests package is very useful and was designed to do just that. Moreover:

- it supports a fully restful API,

- it comes with very short commands:

import requests

resp = requests.get('http://www.mywebsite.com/user')

resp = requests.post('http://www.mywebsite.com/user')

resp = requests.put('http://www.mywebsite.com/user/put')

resp = requests.delete('http://www.mywebsite.com/user/delete')

- it takes a dictionary as argument and

- it has it own built in JSON decoder.

Now that we have the background knowledge needed to understand and implement crawlers let’s build our very first one.

Building Your First Crawler

Let’s build a crawler to extract the 3 top movies of all time of each genre. That sounds like fund, doesn’t? Let’s do that.

First we need to install the following three packages:

requests,beautifulsoupandlxml.

That can be done with the following bash commands:

pip install bs4

pip install requests

pip install lxml

The BeautifulSoup module is used to parse the HTML and extract the information from it. Beautifulsoup does a great job at fixing and formatting the broken HTML codes into a HTML DOM Tree Instance, that is then easy to traverse using Python. The lxml on the other hand, is the parser. We tend to use lxml even for HTML files, since it offers more flexibilities and robustness against HTML syntax errors, such as unclosed tags, improperly nested tags, and missing head or body tags. The only disadvantage of lxml it that it has to be installed separately, which can cause problems in terms of code portability.

There are basically three steps to web scraping:

- Fetching the host site

- Parsing and extracting information

- Saving the information (as csv, json or in a DB)

First let’s start by importing the needed python modules:

import requests

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup as bs

now let’s define the genre and the URL we want to fetch:

genre = 'animation'

link = 'https://www.rottentomatoes.com/top/bestofrt/top_100_' + genre.lower() + '_movies/'

When requesting access to the content of a webpage, sometimes you will get a 403 error response. This is because the server has an anti-crawler installed. To overcome it, you need to simulate the browser header:

headers = {

'user-agent':

'Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 6.1; Win64; x64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/52.0.2743.82 Safari/537.36',

'Cache-Control':'no-cache'

}

# requesting connection with the target link

r = requests.get(link, headers=headers, timeout=20)

Let’s print the response status code from the server, to see if the page was downloaded successfully:

print(f"Response status code: {r.status_code}")

Response status code: 200

A status code 200 means that the page downloaded successfully.

Now we can create our BeautifulSoup object:

soup = bs(r.text, "lxml")

BeautifulSoup module comes with three methods to find elements:

findall(): find all nodesfind(): find a single nodeselect(): CSS Selector

In order to extract the needed information we have to understand the DOM structure of the target webpage and locate the element tag of the movie titles. To do so, we use the browser devtool as shown below:

As we can see, all the movies are listed under the element table with the class attribute table and the titles are under the element a with the class attribute unstyled articleLink:

movies = soup.find('table', class_="table").find_all('a', class_="unstyled articleLink")

That’s it we are done.

Let’s get it all together:

import requests

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup as bs

def top_100_movies(genre):

headers = {

'user-agent':

'Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 6.1; Win64; x64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/52.0.2743.82 Safari/537.36',

'Cache-Control':'no-cache'

}

link = 'https://www.rottentomatoes.com/top/bestofrt/top_100_' + genre.lower() + '_movies/'

movie_list = []

r = requests.get(link, headers=headers, timeout=20)

soup = bs(r.text, "lxml")

movies = soup.find('table', class_="table").find_all('a', class_="unstyled articleLink")

for movie in movies:

movie_list.append(movie.getText().strip())

return movie_list

Because it is prettier in a function and it’s more useful in case you are looking for all time best movies of another genre or all genres such as below:

genres = ['animation', 'horror', 'drama', 'comedy',

'classics', 'documentary', 'romance',

'mystery__suspense', 'action__adventure',

'science_fiction__fantasy','art_house__international']

# 3 top movies in each category

for genre in genres:

print(f"{genre.title().replace('__', ' & ')}: {', '.join(top_100_movies(genre)[:3])}.")

Animation: Toy Story 4 (2019), Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse (2018), Inside Out (2015).

Horror: Us (2019), Get Out (2017), The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari) (1920).

Drama: Black Panther (2018), Citizen Kane (1941), Parasite (Gisaengchung) (2019).

Comedy: It Happened One Night (1934), Modern Times (1936), Toy Story 4 (2019).

Classics: It Happened One Night (1934), Modern Times (1936), Citizen Kane (1941).

Documentary: Won't You Be My Neighbor? (2018), I Am Not Your Negro (2017), Apollo 11 (2019).

Romance: It Happened One Night (1934), Casablanca (1942), The Philadelphia Story (1940).

Mystery & Suspense: Citizen Kane (1941), Knives Out (2019), Us (2019).

Action & Adventure: Black Panther (2018), Avengers: Endgame (2019), Mission: Impossible - Fallout (2018).

Science_Fiction & Fantasy: Black Panther (2018), The Wizard of Oz (1939), Avengers: Endgame (2019).

Art_House & International: Parasite (Gisaengchung) (2019), The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari) (1920), Seven Samurai (Shichinin no Samurai) (1956).

I hope that wasn’t too confusing. At least you’ve got a nice list of movies to watch next.

If you want to learn more about web scraping you can visit the following repos.

References

- CS 142: Web Applications, by John Ousterhout, Stanford University

- Digitalocean community tutorials

- Mitchell, R. 2018. Web Scraping with Python: Collecting More Data from the Modern Web. O’Reilly Media.

Python Web Crawler BeautifulSoup