Customer Segmentation and Profiling: A Managerial Approach

Introduction

In our previous tutorial on RFM analysis, we used hierarchical clustering to discover natural groupings in customer behavior. Today we explore the other side: managerial segmentation, where business leaders make deliberate choices about how to divide their market based on strategic objectives.

Treating all customers the same way guarantees mediocrity. Different customers have different needs, budgets, and buying patterns. Segmentation helps you match your approach to these differences.

Two Philosophies of Segmentation

Post-hoc (exploratory) segmentation discovers patterns you didn’t know existed. You feed the algorithm your data and see what groupings emerge.

A priori (prescriptive) segmentation defines segments upfront according to business logic, then assigns customers to them. This managerial approach is transparent, easy to implement, and aligns directly with business decisions. The downside: you might miss patterns not obvious to human judgment.

Best practice often combines both: use statistical methods to discover patterns, then implement simple rule-based segments for operations.

Defining Our Segmentation Goal

We want to predict which customers are most likely to purchase again. Recency captures purchase likelihood: someone who bought three weeks ago is fundamentally different from someone whose last purchase was three years ago.

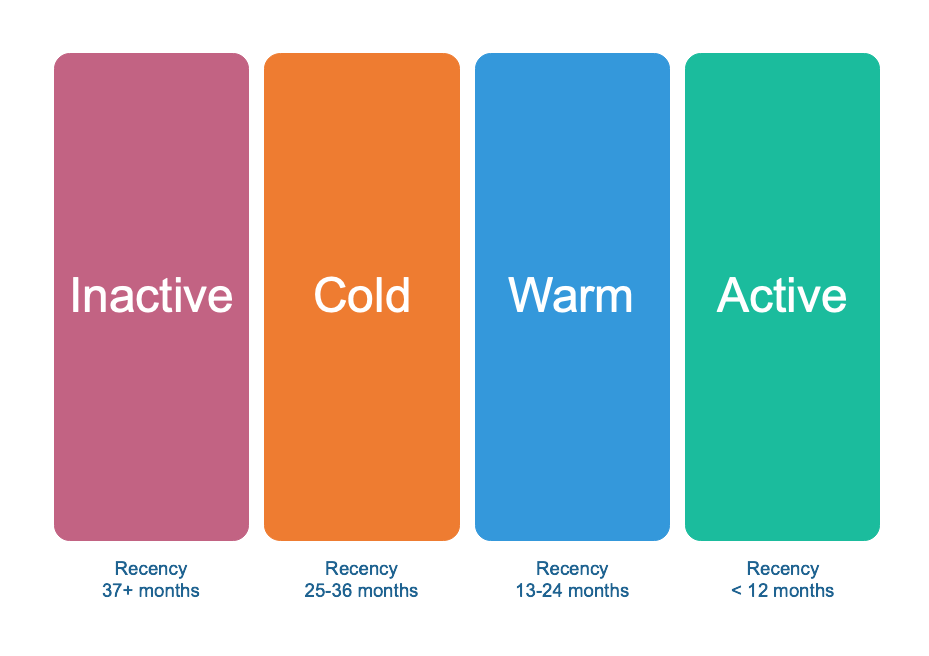

Four basic groups based on recency:

Active customers: last purchase within 12 months. Engaged and likely to buy again.

Warm customers: last purchased 13-24 months ago. Cooling off, need reengagement.

Cold customers: 25-36 months since purchase. Distant relationship, expensive to reactivate.

Inactive customers: over three years. Essentially lost.

A single variable rarely captures enough nuance. We’re leaving money on the table if we treat all active customers the same way, regardless of whether they spend $20 or $200 per purchase.

Enriching the Model with RFM

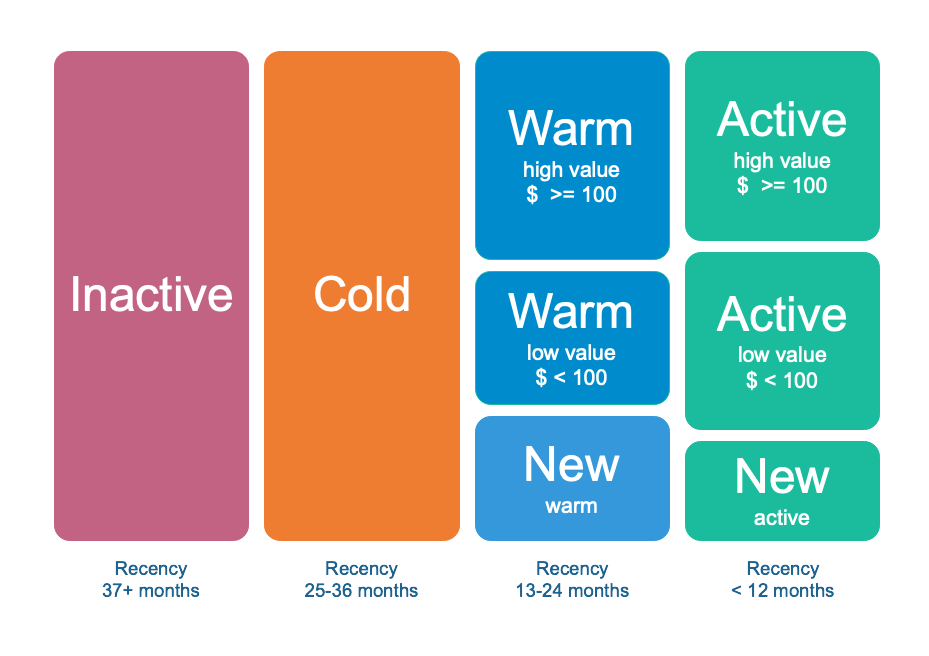

We add frequency and monetary value. New customers require different treatment than loyal ones. High-value customers ($100+ average) deserve more personalized attention than low-value customers.

This leads to eight segments:

- Inactive and Cold: single segments (too expensive to subdivide)

- Warm: new warm, warm low-value, warm high-value

- Active: new active, active low-value, active high-value

The $100 threshold sits where customers demonstrate substantially different value potential. Adjust thresholds to match your industry’s buying rhythms.

Building the Segmentation in Python

Let’s implement this framework with the same dataset we used in our previous tutorial. We have 51,243 transactions from 18,417 unique customers spanning January 2005 through December 2015.

# Load required libraries

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import squarify

from tabulate import tabulate

# Set up our environment

pd.options.display.float_format = '{:,.2f}'.format

plt.rcParams["figure.figsize"] = (12, 8)

# Load the dataset

columns = ['customer_id', 'purchase_amount', 'date_of_purchase']

df = pd.read_csv('purchases.txt', header=None, sep='\t', names=columns)

# Quick look at sample records

df.sample(n=5, random_state=57)

customer_id purchase_amount date_of_purchase

4510 8060 30.00 2014-12-24

17761 109180 50.00 2009-11-25

39110 9830 30.00 2007-06-12

37183 56400 60.00 2009-09-30

33705 41290 60.00 2007-08-21

The data looks clean and ready to work with. Now we prepare our time-based calculations:

# Convert dates to datetime objects

df['date_of_purchase'] = pd.to_datetime(df['date_of_purchase'], format='%Y-%m-%d')

# Extract year for potential cohort analysis

df['year_of_purchase'] = df['date_of_purchase'].dt.year

# Calculate days since each purchase (using Jan 1, 2016 as reference)

basedate = pd.Timestamp('2016-01-01')

df['days_since'] = (basedate - df['date_of_purchase']).dt.days

# Check our work

df.info()

<class 'pandas.core.frame.DataFrame'>

RangeIndex: 51243 entries, 0 to 51242

Data columns (total 5 columns):

# Column Non-Null Count Dtype

--- ------ -------------- -----

0 customer_id 51243 non-null int64

1 purchase_amount 51243 non-null float64

2 date_of_purchase 51243 non-null datetime64[ns]

3 year_of_purchase 51243 non-null int64

4 days_since 51243 non-null int64

dtypes: datetime64[ns](1), float64(1), int64(3)

memory usage: 2.0 MB

Perfect. Everything is properly typed and ready for analysis.

Computing RFM Metrics

Now we aggregate our transaction-level data into customer-level metrics. For each customer, we need three values: how recently they purchased (minimum days since), how frequently they purchase (count of transactions), and how much they typically spend (average purchase amount).

We also want to track when each customer made their first purchase. This helps us identify truly new customers versus those who are simply returning after a long absence.

# Calculate RFM metrics using native pandas

customers = df.groupby('customer_id').agg({

'days_since': ['min', 'max'], # Min = recency, Max = first purchase

'customer_id': 'count', # Count = frequency

'purchase_amount': 'mean' # Mean = average spending

})

# Flatten column names and rename for clarity

customers.columns = ['recency', 'first_purchase', 'frequency', 'amount']

customers = customers.reset_index()

# Display summary statistics

print(tabulate(customers.describe(), headers='keys', tablefmt='psql', floatfmt='.2f'))

+-------+---------------+-----------+------------------+-------------+----------+

| | customer_id | recency | first_purchase | frequency | amount |

|-------+---------------+-----------+------------------+-------------+----------|

| count | 18417.00 | 18417.00 | 18417.00 | 18417.00 | 18417.00 |

| mean | 137574.24 | 1253.04 | 1984.01 | 2.78 | 57.79 |

| std | 69504.61 | 1081.44 | 1133.41 | 2.94 | 154.36 |

| min | 10.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 5.00 |

| 25% | 81990.00 | 244.00 | 988.00 | 1.00 | 21.67 |

| 50% | 136430.00 | 1070.00 | 2087.00 | 2.00 | 30.00 |

| 75% | 195100.00 | 2130.00 | 2992.00 | 3.00 | 50.00 |

| max | 264200.00 | 4014.00 | 4016.00 | 45.00 | 4500.00 |

+-------+---------------+-----------+------------------+-------------+----------+

These statistics tell important stories. The median customer last purchased 1,070 days ago (nearly three years), has made only two purchases total, and averages $30 per transaction. This is why segmentation matters. That median customer probably needs different treatment than the customer who made 45 purchases averaging $4,500 each.

Let’s look at the first few customers:

print(tabulate(customers.head(), headers='keys', tablefmt='psql', floatfmt='.2f'))

+----+---------------+-----------+------------------+-------------+----------+

| | customer_id | recency | first_purchase | frequency | amount |

|----+---------------+-----------+------------------+-------------+----------|

| 0 | 10 | 3829.00 | 3829.00 | 1.00 | 30.00 |

| 1 | 80 | 343.00 | 3751.00 | 7.00 | 71.43 |

| 2 | 90 | 758.00 | 3783.00 | 10.00 | 115.80 |

| 3 | 120 | 1401.00 | 1401.00 | 1.00 | 20.00 |

| 4 | 130 | 2970.00 | 3710.00 | 2.00 | 50.00 |

+----+---------------+-----------+------------------+-------------+----------+

Customer 90 stands out immediately. Ten purchases averaging $115.80, with the last one 758 days ago. That’s a valuable customer who’s gone quiet. Understanding why customers like this stop buying becomes strategically important.

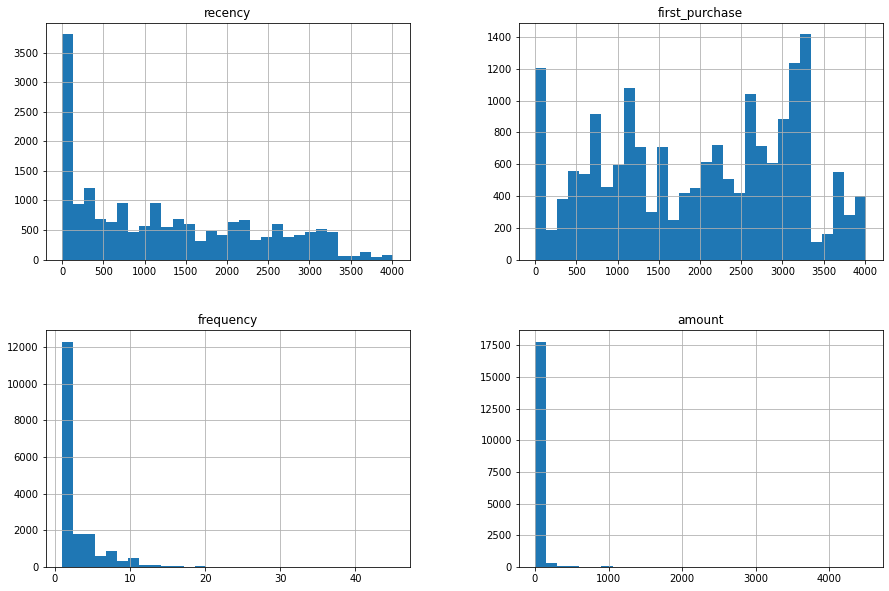

Let’s visualize the distributions of our RFM variables:

# Create histogram grid for RFM variables

customers.iloc[:, 1:].hist(bins=30, figsize=(15, 10))

plt.tight_layout()

plt.savefig('rfm_distributions.png', dpi=150, bbox_inches='tight')

plt.show()

The distributions reveal the same patterns we saw in our clustering analysis. Recency spreads relatively evenly with a spike of recent activity. Frequency is heavily right-skewed with most customers making few purchases. The monetary distribution clusters in the low range with a long tail of high spenders. These patterns justify our decision to create distinct high-value and low-value segments.

Building the Four-Segment Base Model

We start with the simplest version: segmenting purely on recency. This foundation helps us understand the basic health of our customer base before we add complexity.

The segmentation logic proceeds from most distant to most recent. We identify inactive customers first (those who haven’t purchased in over three years), then work our way forward through cold, warm, and finally active customers.

# Initialize segment column

customers['segment'] = None

# Segment 1: Inactive (more than 3 years since last purchase)

customers.loc[customers['recency'] > 365*3, 'segment'] = 'inactive'

# Segment 2: Cold (2-3 years since last purchase)

customers.loc[(customers['recency'] <= 365*3) &

(customers['recency'] > 365*2), 'segment'] = 'cold'

# Segment 3: Warm (1-2 years since last purchase)

customers.loc[(customers['recency'] <= 365*2) &

(customers['recency'] > 365), 'segment'] = 'warm'

# Segment 4: Active (less than 1 year since last purchase)

customers.loc[customers['recency'] <= 365, 'segment'] = 'active'

# Count customers in each segment

segment_counts = customers['segment'].value_counts()

print(segment_counts)

inactive 9158

active 5398

warm 1958

cold 1903

Name: segment, dtype: int64

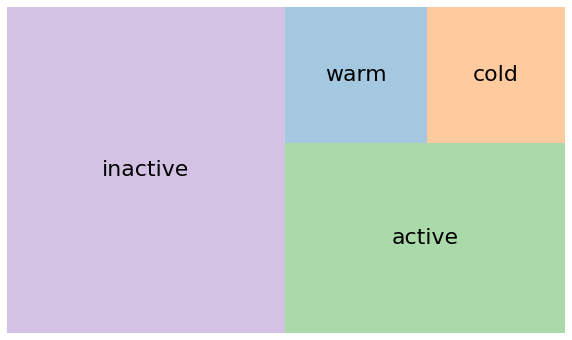

These numbers reveal a troubling pattern. Nearly half our customer base (9,158 out of 18,417) hasn’t purchased in over three years. They’re effectively lost. Another 1,903 customers are cold and at serious risk. That’s 11,061 customers (60% of the total) who are either gone or going.

On the positive side, we have 5,398 active customers and 1,958 warm customers still in play. These 7,356 customers represent our real opportunity. They’re still engaged or recently engaged, and interventions with them are likely to be cost-effective.

Before moving forward, we need to understand why so many customers became inactive. This requires deeper investigation: reviewing customer service records, analyzing product quality issues, benchmarking competitor offerings, and potentially surveying lost customers. Understanding the causes of churn must precede any reactivation strategy. Throwing marketing dollars at inactive customers without addressing root causes wastes money.

Let’s visualize the segment sizes:

# Create treemap visualization

plt.figure(figsize=(10, 6))

plt.rcParams.update({'font.size': 18})

squarify.plot(

sizes=segment_counts,

label=segment_counts.index,

color=['#9b59b6', '#2ecc71', '#3498db', '#e67e22'],

alpha=0.6,

text_kwargs={'fontsize': 16, 'weight': 'bold'}

)

plt.title('Customer Segments by Recency', fontsize=20, pad=20)

plt.axis('off')

plt.tight_layout()

plt.savefig('four_segments_treemap.png', dpi=150, bbox_inches='tight')

plt.show()

The treemap makes the imbalance viscerally clear. That massive purple block of inactive customers dominates the visualization. This is your wake-up call about customer retention. Every business loses customers, but losing 50% to inactivity suggests systematic problems worth investigating.

Expanding to Eight Segments

The four-segment model provides a foundation, but it treats all active customers identically. A customer who made their first purchase two weeks ago receives the same classification as someone who’s been buying regularly for five years. A customer spending $25 per order gets grouped with someone spending $250. We’re leaving strategic opportunities on the table.

Let’s add nuance by incorporating frequency and monetary value, focusing on our active and warm segments where marketing investments are most likely to pay off.

We use numpy’s select function to handle the segmentation logic cleanly. This approach avoids the overlapping condition problems that plague sequential if-then statements:

# Define our segmentation conditions and labels

conditions = [

customers['recency'] > 365*3,

(customers['recency'] <= 365*3) & (customers['recency'] > 365*2),

# Warm segment subdivisions

(customers['segment'] == 'warm') & (customers['first_purchase'] <= 365*2),

(customers['segment'] == 'warm') & (customers['amount'] >= 100),

(customers['segment'] == 'warm') & (customers['amount'] < 100),

# Active segment subdivisions

(customers['segment'] == 'active') & (customers['first_purchase'] <= 365),

(customers['segment'] == 'active') & (customers['amount'] >= 100),

(customers['segment'] == 'active') & (customers['amount'] < 100)

]

choices = [

'inactive',

'cold',

'new warm',

'warm high value',

'warm low value',

'new active',

'active high value',

'active low value'

]

customers['segment'] = np.select(conditions, choices, default=customers['segment'])

# Count customers in each refined segment

refined_counts = customers['segment'].value_counts()

print(refined_counts)

inactive 9158

active low value 3313

cold 1903

new active 1512

new warm 938

warm low value 901

active high value 573

warm high value 119

Name: segment, dtype: int64

These refined segments tell richer stories. Among our 5,398 active customers, 1,512 are brand new (first purchase within the year). They need welcome campaigns and second-purchase incentives to cement the relationship. Another 3,313 are low-value repeat customers who might respond well to volume discounts or bundles. The 573 high-value active customers are your VIPs who deserve personalized service and exclusive offers.

The warm segment shows similar patterns. We have 938 customers who made their first (and only) purchase 13-24 months ago. They tried once and never came back. That requires investigation. Why didn’t they return? Meanwhile, 901 warm low-value customers need automated reengagement, while the 119 warm high-value customers justify personal outreach.

Let’s create a ordered categorical variable to display these segments logically:

# Create ordered categorical for better sorting and display

segment_order = [

'inactive',

'cold',

'warm high value',

'warm low value',

'new warm',

'active high value',

'active low value',

'new active'

]

customers['segment'] = pd.Categorical(

customers['segment'],

categories=segment_order,

ordered=True

)

# Sort by segment for better viewing

customers_sorted = customers.sort_values('segment')

# Display sample from each segment

print("\nFirst 5 customers (inactive segment):")

print(tabulate(

customers_sorted[['customer_id', 'segment']].head(),

headers='keys',

tablefmt='psql',

showindex=False

))

print("\nLast 5 customers (new active segment):")

print(tabulate(

customers_sorted[['customer_id', 'segment']].tail(),

headers='keys',

tablefmt='psql',

showindex=False

))

First 5 customers (inactive segment):

+---------------+------------+

| customer_id | segment |

|---------------+------------|

| 10 | inactive |

| 119690 | inactive |

| 119710 | inactive |

| 119720 | inactive |

| 119730 | inactive |

+---------------+------------+

Last 5 customers (new active segment):

+---------------+--------------+

| customer_id | segment |

|---------------+--------------|

| 252380 | new active |

| 252370 | new active |

| 252360 | new active |

| 252450 | new active |

| 264200 | new active |

+---------------+--------------+

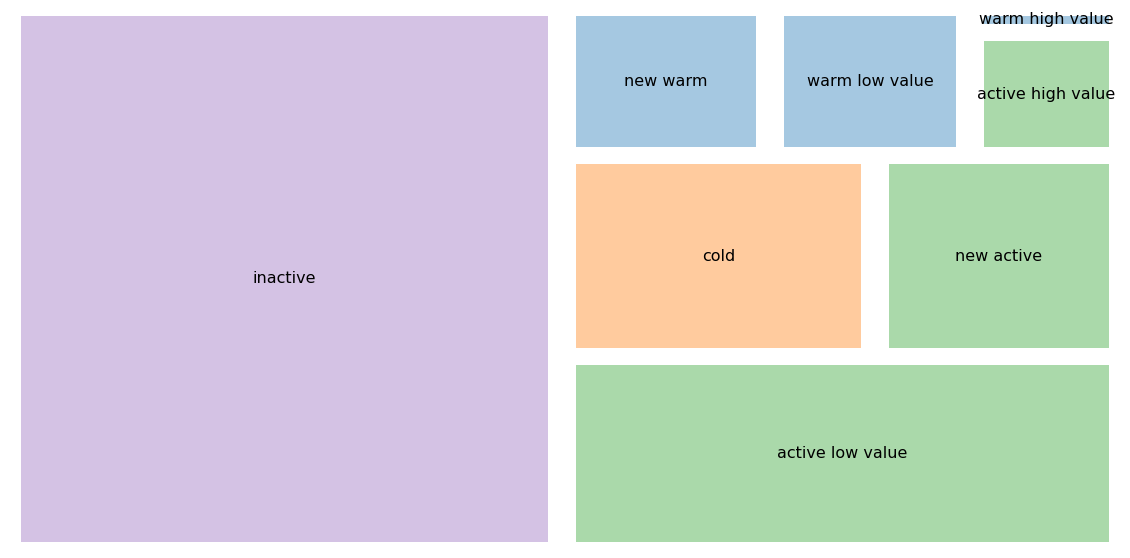

Now let’s visualize the complete eight-segment model:

# Create color scheme that groups related segments

colors = [

'#9b59b6', # inactive - purple

'#e67e22', # cold - orange

'#3498db', # warm high value - blue

'#2ecc71', # warm low value - green

'#3498db', # new warm - blue

'#3498db', # active high value - blue

'#2ecc71', # active low value - green

'#3498db' # new active - blue

]

plt.figure(figsize=(16, 10))

plt.rcParams.update({'font.size': 14})

squarify.plot(

sizes=refined_counts.reindex(segment_order),

label=segment_order,

color=colors,

alpha=0.6,

pad=True,

text_kwargs={'fontsize': 13, 'weight': 'bold'}

)

plt.title('Eight-Segment RFM Customer Model', fontsize=20, pad=20)

plt.axis('off')

plt.tight_layout()

plt.savefig('eight_segments_treemap.png', dpi=150, bbox_inches='tight')

plt.show()

The color coding helps group related segments. Blue shades indicate higher engagement or value segments worth significant investment. Green shows lower-value but still active relationships. Orange represents customers at risk. Purple marks those who are lost.

Creating Buyer Personas

Personas transform abstract segment characteristics into concrete, relatable characters. For example, “active high value” becomes “Premium Paula,” a 35-45 year old professional who values quality over price. Your marketing to Paula emphasizes convenience and exclusivity, not discounts.

“New active” might be “First-Timer Frank,” a price-conscious 25-35 year old susceptible to buyer’s remorse. Frank needs reassurance and gentle nudges toward a second purchase.

Marketing teams can ask “What would Paula want?” instead of referencing “Segment 6.” Building comprehensive personas requires demographic information, psychographic profiles, and purchase motivations beyond transaction data.

Strategic Implications for Each Segment

Inactive: Stop spending money on them unless previously very high-value. Low-cost automated reactivation only.

Cold: Triage by historical value. High-value cold customers might justify personalized outreach. Low-value get automated “we miss you” campaigns.

Warm low-value: Efficient, automated reengagement. Time-limited discounts, personalization at scale.

Warm high-value: Personal attention. Direct outreach to understand why they stopped buying.

New warm: Survey their experience. Offer a compelling second chance. If no response, let them fade.

Active low-value: Keep engaged with regular communications. Encourage larger baskets through bundles.

Active high-value: White-glove treatment. VIP programs, exclusive access, ask for referrals.

New active: Critical window. Second purchase incentives, welcome campaigns, make them feel valued.

Comparing Statistical and Managerial Approaches

Statistical clustering discovers patterns you didn’t specify. Managerial segmentation implements business logic directly and is transparent, fast, and easy to adjust.

Best practice combines both: use statistical methods periodically to discover patterns and validate assumptions, then implement simple rule-based segments for operations. For operational deployment, managerial segmentation wins because it runs fast, updates easily, and requires no data science team.

Implementation Considerations

Automation: Segmentation code needs to run automatically, updating segment assignments as new purchases occur.

Integration: Segments must flow into email marketing, CRM, and advertising platforms consistently.

Seasonality: A customer who looks inactive in February might simply buy holiday gifts in December.

Monitoring: Track segment composition changes. If campaigns don’t achieve expected results across segments, something is wrong.

Conclusion

We started with a basic recency-based model revealing that 50% of customers had become inactive. We enriched this with frequency and monetary dimensions, creating eight segments with specific marketing strategies for each.

The power lies in business alignment. When segmentation directly reflects decisions you need to make (who to target, how much to invest, what message to send), implementation becomes straightforward.

The goal is actionable segmentation that improves resource allocation. Often, the simplest approach your organization can actually implement beats the most elegant solution that never makes it into production.

References

-

Lilien, Gary L, Arvind Rangaswamy, and Arnaud De Bruyn. 2017. Principles of Marketing Engineering and Analytics. State College, PA: DecisionPro.

-

Piercy, Nigel F., and Neil A. Morgan. 1993. “Strategic and Operational Market Segmentation: A Managerial Analysis.” Journal of Strategic Marketing 1 (2): 123-40. https://doi.org/10.1080/09652549300000008.

-

Wind, Yoram. 1978. “Issues and Advances in Segmentation Research.” Journal of Marketing Research 15 (3): 317-34. https://doi.org/10.2307/3150580.

-

Armstrong, G.M., S. Adam, S.M. Denize, M. Volkov, and P. Kotler. 2017. Principles of Marketing. Pearson Australia.

-

Laureiro-Martínez, Daniella, Stefano Brusoni, Nicola Canessa, and Maurizio Zollo. 2015. “Understanding the Exploration-Exploitation Dilemma: An fMRI Study of Attention Control and Decision-Making Performance.” Strategic Management Journal 36 (3): 319-38. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2221.

-

Arnaud De Bruyn. Foundations of Marketing Analytics (MOOC). Coursera.

-

Dataset from Github repo. Accessed 15 December 2021.

Data Science