From RFM Analysis to Predictive Scoring Models

Introduction

We’ve come a long way in understanding our customers. In our first tutorial, we used hierarchical clustering to discover natural groupings in customer behavior, letting the data reveal patterns we might have missed. In the second tutorial, we flipped the script and implemented managerial segmentation, where business logic drives the groupings directly.

Both approaches answered the question “who are my customers right now?” Today we’re tackling something more ambitious: predicting the future. Which customers will purchase next year? How much will they spend? These aren’t just interesting academic questions. They’re the foundation for smart resource allocation, inventory planning, and targeted marketing campaigns.

Today we’re building a predictive scoring system that combines everything from our previous tutorials. We’ll use RFM segmentation as the foundation, then layer on statistical models to predict both purchase probability and purchase amount. The result is a customer score that tells you where to focus your marketing investment for maximum return.

The Analytical Framework

Our approach uses a two-stage modeling process. First, we predict whether a customer will make any purchase at all in the next period. This is a classification problem: active or inactive. Second, for those predicted to be active, we estimate how much they’ll spend. This is a regression problem with continuous dollar values.

Why separate these? Purchase probability depends heavily on recency and engagement patterns. Purchase amount depends more on historical spending levels. Trying to predict dollar amounts directly for all customers (including those who won’t buy anything) creates a messy model with poor performance.

We’ll validate our approach using retrospective segmentation: analyze our 2014 customer base as if we were living in 2014, build models to predict 2015 behavior, then check how accurate those predictions were. This gives us confidence before making real 2016 predictions.

Setting Up Our Analysis

Let’s start with our familiar dataset: 51,243 transactions from 18,417 unique customers spanning January 2005 through December 2015. We’ll be more disciplined about our code this time. Since we’ll be running RFM segmentation multiple times (for 2014, 2015, and validation), we’ll create reusable functions instead of copying code.

# Import required libraries

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import statsmodels.api as sm

import squarify

from scipy import stats

from tabulate import tabulate

# Set up environment

pd.options.display.float_format = '{:,.2f}'.format

plt.rcParams["figure.figsize"] = (12, 8)

# Load the dataset

columns = ['customer_id', 'purchase_amount', 'date_of_purchase']

df = pd.read_csv('purchases.txt', header=None, sep='\t', names=columns)

# Convert to datetime and create time-based features

df['date_of_purchase'] = pd.to_datetime(df['date_of_purchase'], format='%Y-%m-%d')

df['year_of_purchase'] = df['date_of_purchase'].dt.year

# Set reference date for calculating recency

basedate = pd.Timestamp('2016-01-01')

df['days_since'] = (basedate - df['date_of_purchase']).dt.days

Building Reusable Segmentation Functions

Rather than copy-pasting segmentation logic three times, we’ll create a clean function that handles the entire RFM calculation and segmentation process. This makes our code more maintainable and reduces errors.

def calculate_rfm(dataframe, reference_date=None, days_lookback=None):

"""

Calculate RFM metrics for customers.

Parameters:

-----------

dataframe : DataFrame

Transaction data with customer_id, purchase_amount, days_since

reference_date : Timestamp, optional

Date to calculate recency from (default: None, uses all data)

days_lookback : int, optional

Only consider transactions within this many days (default: None, uses all)

Returns:

--------

DataFrame with customer_id and RFM metrics

"""

# Filter data if lookback specified

if days_lookback is not None:

df_filtered = dataframe[dataframe['days_since'] > days_lookback].copy()

# Adjust days_since relative to the lookback period

df_filtered['days_since'] = df_filtered['days_since'] - days_lookback

else:

df_filtered = dataframe.copy()

# Calculate RFM metrics using native pandas

rfm = df_filtered.groupby('customer_id').agg({

'days_since': ['min', 'max'], # Min = recency, Max = first purchase

'customer_id': 'count', # Count = frequency

'purchase_amount': ['mean', 'max'] # Average and max spending

})

# Flatten column names

rfm.columns = ['recency', 'first_purchase', 'frequency', 'avg_amount', 'max_amount']

rfm = rfm.reset_index()

return rfm

def segment_customers(rfm_data):

"""

Segment customers based on RFM metrics using managerial rules.

Parameters:

-----------

rfm_data : DataFrame

Customer data with RFM metrics

Returns:

--------

DataFrame with added 'segment' column

"""

customers = rfm_data.copy()

# Use numpy select for clean, non-overlapping logic

conditions = [

customers['recency'] > 365 * 3,

(customers['recency'] <= 365 * 3) & (customers['recency'] > 365 * 2),

(customers['recency'] <= 365 * 2) & (customers['recency'] > 365) &

(customers['first_purchase'] <= 365 * 2),

(customers['recency'] <= 365 * 2) & (customers['recency'] > 365) &

(customers['avg_amount'] >= 100),

(customers['recency'] <= 365 * 2) & (customers['recency'] > 365) &

(customers['avg_amount'] < 100),

(customers['recency'] <= 365) & (customers['first_purchase'] <= 365),

(customers['recency'] <= 365) & (customers['avg_amount'] >= 100),

(customers['recency'] <= 365) & (customers['avg_amount'] < 100)

]

choices = [

'inactive',

'cold',

'new warm',

'warm high value',

'warm low value',

'new active',

'active high value',

'active low value'

]

customers['segment'] = np.select(conditions, choices, default='other')

# Convert to ordered categorical

segment_order = [

'inactive', 'cold', 'warm high value', 'warm low value', 'new warm',

'active high value', 'active low value', 'new active'

]

customers['segment'] = pd.Categorical(

customers['segment'],

categories=segment_order,

ordered=True

)

return customers.sort_values('segment')

The calculate_rfm function handles aggregation and works with different time windows. The segment_customers function applies our business rules using numpy’s select function.

Understanding Our Current Customer Base

Let’s apply our functions to understand the current state of affairs as of the end of 2015:

# Calculate RFM for all customers as of end of 2015

customers_2015 = calculate_rfm(df)

customers_2015 = segment_customers(customers_2015)

# Display segment distribution

segment_counts = customers_2015['segment'].value_counts()

print(segment_counts)

inactive 9158

active low value 3313

cold 1903

new active 1512

new warm 938

warm low value 901

active high value 573

warm high value 119

Name: segment, dtype: int64

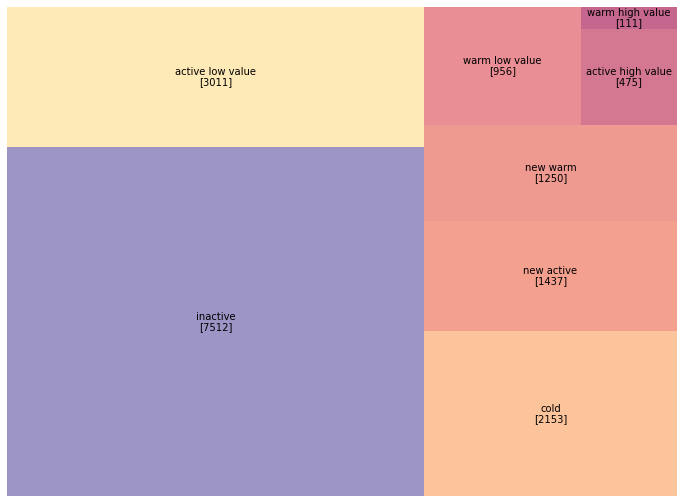

Half our customer base has gone inactive. Focusing on the 7,356 customers in warm and active segments makes more strategic sense than trying to resurrect the 9,158 inactive ones.

Let’s visualize this with our familiar treemap:

# Create treemap visualization

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(14, 9))

colors = ['#9b59b6', '#e67e22', '#3498db', '#2ecc71', '#3498db',

'#3498db', '#2ecc71', '#3498db']

squarify.plot(

sizes=segment_counts.reindex(customers_2015['segment'].cat.categories),

label=customers_2015['segment'].cat.categories,

color=colors,

alpha=0.6,

text_kwargs={'fontsize': 13, 'weight': 'bold'}

)

plt.title('Customer Segments as of December 2015', fontsize=18, pad=20)

plt.axis('off')

plt.tight_layout()

plt.savefig('segments_2015_treemap.png', dpi=150, bbox_inches='tight')

plt.show()

Now we need to understand which segments actually drove revenue in 2015. This tells us whether our segmentation captures value meaningfully:

# Calculate 2015 revenue by customer

revenue_2015 = df[df['year_of_purchase'] == 2015].groupby('customer_id').agg({

'purchase_amount': 'sum'

}).rename(columns={'purchase_amount': 'revenue_2015'})

# Merge with customer segments (left join to include all customers)

actual = customers_2015.merge(revenue_2015, on='customer_id', how='left')

actual['revenue_2015'] = actual['revenue_2015'].fillna(0)

# Calculate average revenue by segment

segment_revenue = actual.groupby('segment', observed=True)['revenue_2015'].mean()

print("\nAverage 2015 Revenue by Segment:")

print(segment_revenue.round(2))

Average 2015 Revenue by Segment:

segment

inactive 0.00

cold 0.00

warm high value 0.00

warm low value 0.00

new warm 0.00

active high value 323.57

active low value 52.31

new active 79.17

Name: revenue_2015, dtype: float64

Only active customers generated 2015 revenue (by definition). The active high value segment, just 3% of customers, generated 71% of total revenue.

The Retrospective Validation Strategy

Before making 2016 predictions we can’t validate, let’s build models using 2014 data to predict 2015 behavior. We already know what happened in 2015, so we can measure accuracy. We recreate January 1, 2015 by filtering our data to only include transactions through December 31, 2014.

# Calculate RFM as of end of 2014 (ignoring all 2015 transactions)

# This requires looking back 365 days from our reference date

customers_2014 = calculate_rfm(df, days_lookback=365)

customers_2014 = segment_customers(customers_2014)

# Visualize 2014 segments

segment_counts_2014 = customers_2014['segment'].value_counts()

print("\n2014 Segment Distribution:")

print(segment_counts_2014)

2014 Segment Distribution:

inactive 8602

active low value 3094

cold 1923

new active 1474

new warm 936

warm low value 835

active high value 476

warm high value 108

Name: segment, dtype: int64

Notice the differences from 2015: the active high value segment grew from 476 to 573 customers (20% growth). Let’s visualize the year-over-year shift:

# Create comparison visualization

fig, (ax1, ax2) = plt.subplots(1, 2, figsize=(16, 7))

# 2014 segments

squarify.plot(

sizes=segment_counts_2014.reindex(customers_2014['segment'].cat.categories),

label=customers_2014['segment'].cat.categories,

color=colors,

alpha=0.6,

ax=ax1,

text_kwargs={'fontsize': 11, 'weight': 'bold'}

)

ax1.set_title('Customer Segments - End of 2014', fontsize=16, pad=15)

ax1.axis('off')

# 2015 segments

squarify.plot(

sizes=segment_counts.reindex(customers_2015['segment'].cat.categories),

label=customers_2015['segment'].cat.categories,

color=colors,

alpha=0.6,

ax=ax2,

text_kwargs={'fontsize': 11, 'weight': 'bold'}

)

ax2.set_title('Customer Segments - End of 2015', fontsize=16, pad=15)

ax2.axis('off')

plt.tight_layout()

plt.savefig('segments_comparison.png', dpi=150, bbox_inches='tight')

plt.show()

Building the Training Dataset

We’ll use 2014 customer characteristics (RFM metrics) as features to predict 2015 behavior (whether they purchased and how much they spent).

# Merge 2014 customer data with 2015 revenue (the target variable)

in_sample = customers_2014.merge(revenue_2015, on='customer_id', how='left')

in_sample['revenue_2015'] = in_sample['revenue_2015'].fillna(0)

# Create binary target variable for classification

in_sample['active_2015'] = (in_sample['revenue_2015'] > 0).astype(int)

# Display summary

print(f"\nTraining dataset: {len(in_sample)} customers")

print(f"Active in 2015: {in_sample['active_2015'].sum()} ({in_sample['active_2015'].mean():.1%})")

print(f"\nTarget variable distribution:")

print(in_sample['active_2015'].value_counts())

Training dataset: 16905 customers

Active in 2015: 3886 (23.0%)

Target variable distribution:

0 13019

1 3886

Name: active_2015, dtype: int64

Our dataset contains 16,905 customers who existed in 2014. Of these, 3,886 (23%) made at least one purchase in 2015. This 23% base rate becomes our benchmark. The class imbalance (77% inactive vs. 23% active) is typical in customer analytics.

Predicting Purchase Probability with Logistic Regression

Our first model predicts whether a customer will make any purchase in 2015 based on their 2014 RFM characteristics. We’ll use five features: recency, first purchase date, frequency, average amount, and maximum amount.

# Define the logistic regression model

# Note: We use statsmodels for rich statistical output

formula = "active_2015 ~ recency + first_purchase + frequency + avg_amount + max_amount"

prob_model = sm.Logit.from_formula(formula, in_sample)

# Fit the model

prob_model_fit = prob_model.fit()

# Display results

print(prob_model_fit.summary())

Optimization terminated successfully.

Current function value: 0.365836

Iterations 8

Logit Regression Results

==============================================================================

Dep. Variable: active_2015 No. Observations: 16905

Model: Logit Df Residuals: 16899

Method: MLE Df Model: 5

Date: Pseudo R-squ.: 0.3214

Time: Log-Likelihood: -6184.5

converged: True LL-Null: -9113.9

Covariance Type: nonrobust LLR p-value: 0.000

==================================================================================

coef std err z P>|z| [0.025 0.975]

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Intercept -0.5331 0.044 -12.087 0.000 -0.620 -0.447

recency -0.0020 0.000 -32.748 0.000 -0.002 -0.002

first_purchase -0.0000 0.000 -0.297 0.766 -0.000 0.000

frequency 0.2195 0.015 14.840 0.000 0.191 0.249

avg_amount 0.0004 0.000 1.144 0.253 -0.000 0.001

max_amount -0.0002 0.000 -0.574 0.566 -0.001 0.000

==================================================================================

Recency (coef: -0.0020, z: -32.75) is our strongest predictor. The more days since a customer’s last purchase, the less likely they’ll purchase again.

Frequency (coef: 0.2195, z: 14.84) is our second strongest predictor. Each additional purchase in 2014 increases the likelihood of 2015 activity.

First purchase date, average amount, and maximum amount have p-values above 0.25, meaning they don’t add predictive power beyond what recency and frequency already capture.

The Pseudo R-squared of 0.32 means our model explains about 32% of the variation in purchase behavior. Let’s examine the standardized coefficients:

# Calculate standardized coefficients (z-scores)

standardized_coef = prob_model_fit.params / prob_model_fit.bse

print("\nStandardized Coefficients (z-scores):")

print(standardized_coef.round(2))

Standardized Coefficients (z-scores):

Intercept -12.09

recency -32.75

first_purchase -0.30

frequency 14.84

avg_amount 1.14

max_amount -0.57

dtype: float64

Recency dominates with a z-score of -32.75, followed by frequency at 14.84. Everything else is noise in comparison.

Predicting Purchase Amount with Linear Regression

For customers who do purchase in 2015, how much will they spend? We can only train this model on customers who actually purchased, reducing our sample from 16,905 to 3,886.

# Filter to only customers who were active in 2015

active_customers = in_sample[in_sample['active_2015'] == 1].copy()

print(f"\nActive customer sample: {len(active_customers)} customers")

print("\nSpending distribution:")

print(active_customers['revenue_2015'].describe())

Active customer sample: 3886 customers

Spending distribution:

count 3886.00

mean 92.30

std 217.45

min 5.00

25% 30.00

50% 50.00

75% 100.00

max 4500.00

Name: revenue_2015, dtype: float64

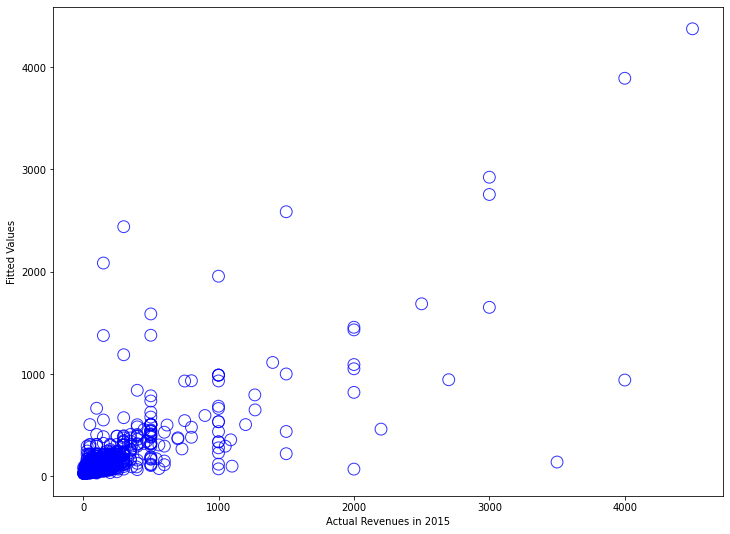

The spending distribution is heavily right-skewed: mean ($92) exceeds median ($50) substantially. This skewness causes problems for OLS regression. Let’s try a naive model first:

# Attempt 1: Predict revenue directly (this will perform poorly)

amount_model_v1 = sm.OLS.from_formula(

"revenue_2015 ~ avg_amount + max_amount",

active_customers

)

amount_model_v1_fit = amount_model_v1.fit()

print(amount_model_v1_fit.summary())

OLS Regression Results

==============================================================================

Dep. Variable: revenue_2015 R-squared: 0.605

Model: OLS Adj. R-squared: 0.605

Method: Least Squares F-statistic: 2979.

Date: Prob (F-statistic): 0.00

Time: Log-Likelihood: -24621.

No. Observations: 3886 AIC: 4.925e+04

Df Residuals: 3883 BIC: 4.927e+04

Df Model: 2

Covariance Type: nonrobust

==============================================================================

coef std err t P>|t| [0.025 0.975]

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Intercept 20.7471 2.381 8.713 0.000 16.079 25.415

avg_amount 0.6749 0.033 20.575 0.000 0.611 0.739

max_amount 0.2923 0.024 12.367 0.000 0.246 0.339

==============================================================================

Omnibus: 5580.836 Durbin-Watson: 2.007

Prob(Omnibus): 0.000 Jarque-Bera (JB): 8162692.709

Skew: 7.843 Prob(JB): 0.00

Kurtosis: 226.980 Cond. No. 315.

==============================================================================

The R-squared of 0.605 looks decent, but the Jarque-Bera test has an astronomically high value (8 million), and skewness of 7.84 confirms severe right-skew. Let’s visualize what’s going wrong:

# Plot actual vs predicted values

fig, axes = plt.subplots(2, 2, figsize=(14, 12))

# Scatter of predictions

axes[0, 0].scatter(

active_customers['revenue_2015'],

amount_model_v1_fit.fittedvalues,

alpha=0.4,

edgecolors='b',

facecolors='none'

)

axes[0, 0].plot([0, 4500], [0, 4500], 'r--', alpha=0.5, label='Perfect prediction')

axes[0, 0].set_xlabel('Actual 2015 Revenue ($)', fontsize=12)

axes[0, 0].set_ylabel('Predicted Revenue ($)', fontsize=12)

axes[0, 0].set_title('Actual vs. Predicted (Linear Model)', fontsize=13)

axes[0, 0].legend()

# Residual plot

residuals = active_customers['revenue_2015'] - amount_model_v1_fit.fittedvalues

axes[0, 1].scatter(

amount_model_v1_fit.fittedvalues,

residuals,

alpha=0.4,

edgecolors='b',

facecolors='none'

)

axes[0, 1].axhline(y=0, color='r', linestyle='--', alpha=0.5)

axes[0, 1].set_xlabel('Predicted Revenue ($)', fontsize=12)

axes[0, 1].set_ylabel('Residuals ($)', fontsize=12)

axes[0, 1].set_title('Residual Plot (Linear Model)', fontsize=13)

# Distribution of residuals

axes[1, 0].hist(residuals, bins=50, edgecolor='black', alpha=0.7)

axes[1, 0].set_xlabel('Residuals ($)', fontsize=12)

axes[1, 0].set_ylabel('Frequency', fontsize=12)

axes[1, 0].set_title('Distribution of Residuals (Linear Model)', fontsize=13)

# Q-Q plot

stats.probplot(residuals, dist="norm", plot=axes[1, 1])

axes[1, 1].set_title('Q-Q Plot (Linear Model)', fontsize=13)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.savefig('linear_model_diagnostics.png', dpi=150, bbox_inches='tight')

plt.show()

The residual plot displays the classic “megaphone” pattern (heteroscedasticity), and the Q-Q plot curves away from the diagonal. Our model makes terrible predictions for high-spending customers.

The Log Transformation Solution

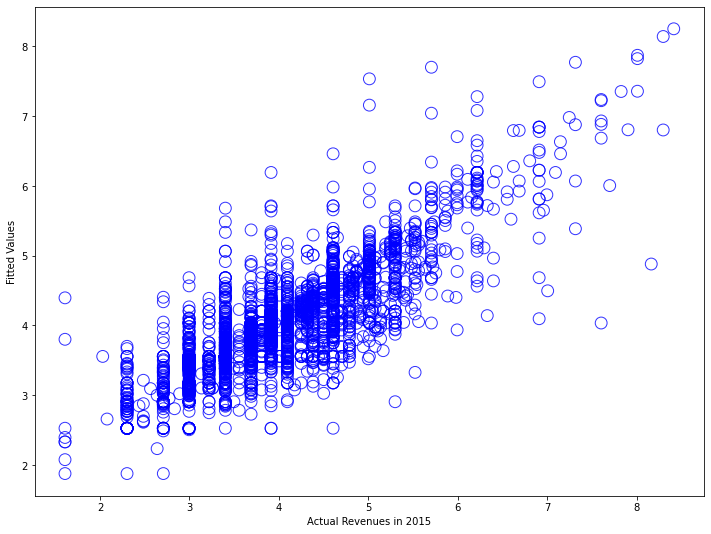

A logarithmic transformation compresses large values and expands small values, creating a more symmetric distribution. It also captures proportional thinking: a customer going from $30 to $60 represents the same proportional change as going from $300 to $600.

Let’s apply the transformation:

# Attempt 2: Log-transformed model

amount_model_v2 = sm.OLS.from_formula(

"np.log(revenue_2015) ~ np.log(avg_amount) + np.log(max_amount)",

active_customers

)

amount_model_v2_fit = amount_model_v2.fit()

print(amount_model_v2_fit.summary())

OLS Regression Results

==============================================================================

Dep. Variable: np.log(revenue_2015) R-squared: 0.693

Model: OLS Adj. R-squared: 0.693

Method: Least Squares F-statistic: 4377.

Date: Prob (F-statistic): 0.00

Time: Log-Likelihood: -2644.6

No. Observations: 3886 AIC: 5295.

Df Residuals: 3883 BIC: 5314.

Df Model: 2

Covariance Type: nonrobust

=======================================================================================

coef std err t P>|z| [0.025 0.975]

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Intercept 0.3700 0.040 9.242 0.000 0.292 0.448

np.log(avg_amount) 0.5488 0.042 13.171 0.000 0.467 0.631

np.log(max_amount) 0.3881 0.038 10.224 0.000 0.314 0.463

==============================================================================

Omnibus: 501.505 Durbin-Watson: 1.961

Prob(Omnibus): 0.000 Jarque-Bera (JB): 3328.833

Skew: 0.421 Prob(JB): 0.00

Kurtosis: 7.455 Cond. No. 42.2

==============================================================================

R-squared increased from 0.605 to 0.693. Skewness fell from 7.84 to 0.42. A 1% increase in average historical spending predicts a 0.55% increase in next-period spending. Let’s examine the diagnostic plots:

# Create diagnostic plots for log-transformed model

fig, axes = plt.subplots(2, 2, figsize=(14, 12))

# Scatter of predictions (in log space)

log_actual = np.log(active_customers['revenue_2015'])

axes[0, 0].scatter(

log_actual,

amount_model_v2_fit.fittedvalues,

alpha=0.4,

edgecolors='b',

facecolors='none'

)

axes[0, 0].plot([log_actual.min(), log_actual.max()],

[log_actual.min(), log_actual.max()],

'r--', alpha=0.5, label='Perfect prediction')

axes[0, 0].set_xlabel('Log(Actual 2015 Revenue)', fontsize=12)

axes[0, 0].set_ylabel('Log(Predicted Revenue)', fontsize=12)

axes[0, 0].set_title('Actual vs. Predicted (Log-Transformed Model)', fontsize=13)

axes[0, 0].legend()

# Residual plot

residuals_log = log_actual - amount_model_v2_fit.fittedvalues

axes[0, 1].scatter(

amount_model_v2_fit.fittedvalues,

residuals_log,

alpha=0.4,

edgecolors='b',

facecolors='none'

)

axes[0, 1].axhline(y=0, color='r', linestyle='--', alpha=0.5)

axes[0, 1].set_xlabel('Log(Predicted Revenue)', fontsize=12)

axes[0, 1].set_ylabel('Residuals', fontsize=12)

axes[0, 1].set_title('Residual Plot (Log-Transformed Model)', fontsize=13)

# Distribution of residuals

axes[1, 0].hist(residuals_log, bins=50, edgecolor='black', alpha=0.7)

axes[1, 0].set_xlabel('Residuals', fontsize=12)

axes[1, 0].set_ylabel('Frequency', fontsize=12)

axes[1, 0].set_title('Distribution of Residuals (Log-Transformed Model)', fontsize=13)

# Q-Q plot

stats.probplot(residuals_log, dist="norm", plot=axes[1, 1])

axes[1, 1].set_title('Q-Q Plot (Log-Transformed Model)', fontsize=13)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.savefig('log_model_diagnostics.png', dpi=150, bbox_inches='tight')

plt.show()

Much better. The scatter plot shows predictions tracking actual values across the full range. The residual plot displays roughly constant variance. The Q-Q plot hugs the diagonal line much more closely.

Validating Model Performance

Let’s generate predictions and compare them to reality:

# Generate predictions for all 2014 customers

in_sample['prob_predicted'] = prob_model_fit.predict(in_sample)

in_sample['log_amount_predicted'] = amount_model_v2_fit.predict(in_sample)

# Transform log predictions back to dollar values

in_sample['amount_predicted'] = np.exp(in_sample['log_amount_predicted'])

# Create combined score: probability × expected amount

in_sample['score_predicted'] = (

in_sample['prob_predicted'] * in_sample['amount_predicted']

)

print("\nPrediction Summary Statistics:")

print("\nProbability of being active:")

print(in_sample['prob_predicted'].describe())

print("\nPredicted spending (if active):")

print(in_sample['amount_predicted'].describe())

print("\nExpected value score:")

print(in_sample['score_predicted'].describe())

Prediction Summary Statistics:

Probability of being active:

count 16905.00

mean 0.22

std 0.25

min 0.00

25% 0.01

50% 0.11

75% 0.40

max 1.00

Name: prob_predicted, dtype: float64

Predicted spending (if active):

count 16905.00

mean 65.63

std 147.89

min 6.54

25% 29.00

50% 35.05

75% 57.30

max 3832.95

Name: amount_predicted, dtype: float64

Expected value score:

count 16905.00

mean 18.83

std 70.21

min 0.00

25% 0.46

50% 4.56

75% 17.96

max 2854.16

Name: score_predicted, dtype: float64

Our model predicts an average 22% probability of purchase, close to the actual 23% base rate. Let’s validate against what actually happened:

# Compare predicted vs actual at different score thresholds

def evaluate_predictions(df, score_threshold):

"""

Evaluate model performance at a given score threshold.

"""

# Identify high-score customers

high_score = df['score_predicted'] > score_threshold

# Calculate metrics

n_targeted = high_score.sum()

n_actually_active = df['active_2015'].sum()

n_correctly_identified = (high_score & (df['active_2015'] == 1)).sum()

precision = n_correctly_identified / n_targeted if n_targeted > 0 else 0

recall = n_correctly_identified / n_actually_active

actual_revenue = df[high_score]['revenue_2015'].sum()

predicted_revenue = df[high_score]['score_predicted'].sum()

return {

'threshold': score_threshold,

'n_targeted': n_targeted,

'n_correct': n_correctly_identified,

'precision': precision,

'recall': recall,

'actual_revenue': actual_revenue,

'predicted_revenue': predicted_revenue,

'revenue_accuracy': actual_revenue / predicted_revenue if predicted_revenue > 0 else 0

}

# Test multiple thresholds

thresholds = [10, 20, 30, 50, 75, 100]

results = [evaluate_predictions(in_sample, t) for t in thresholds]

results_df = pd.DataFrame(results)

print("\nModel Performance at Different Score Thresholds:")

print(tabulate(results_df, headers='keys', tablefmt='psql', floatfmt='.2f', showindex=False))

Model Performance at Different Score Thresholds:

+-----------+-------------+-----------+------------+---------+------------------+--------------------+-------------------+

| threshold | n_targeted | n_correct | precision | recall | actual_revenue | predicted_revenue | revenue_accuracy |

+-----------+-------------+-----------+------------+---------+------------------+--------------------+-------------------+

| 10.00 | 2584.00 | 2384.00 | 0.92 | 0.61 | 186874.00 | 143522.04 | 1.30 |

| 20.00 | 1816.00 | 1743.00 | 0.96 | 0.45 | 157223.00 | 119823.49 | 1.31 |

| 30.00 | 1448.00 | 1417.00 | 0.98 | 0.36 | 139960.00 | 106544.46 | 1.31 |

| 50.00 | 1028.00 | 1016.00 | 0.99 | 0.26 | 115536.00 | 87837.31 | 1.32 |

| 75.00 | 714.00 | 710.00 | 0.99 | 0.18 | 93913.00 | 70875.90 | 1.33 |

| 100.00 | 521.00 | 520.00 | 1.00 | 0.13 | 78168.00 | 58636.32 | 1.33 |

+-----------+-------------+-----------+------------+---------+------------------+--------------------+-------------------+

At a score threshold of $50, we identify 1,028 customers as high-value targets. Of these, 1,016 (99%) actually purchased in 2015. These 1,028 customers (6% of the database) generated $115,536 in actual revenue (32% of total). The revenue accuracy ratio stays around 1.3, meaning actual revenue exceeded predictions by about 30%. Let’s visualize the calibration:

# Create calibration plot

fig, axes = plt.subplots(1, 2, figsize=(15, 6))

# Binned calibration plot for probability predictions

from scipy.stats import binned_statistic

bins = 10

bin_means, bin_edges, bin_numbers = binned_statistic(

in_sample['prob_predicted'],

in_sample['active_2015'],

statistic='mean',

bins=bins

)

bin_centers = (bin_edges[:-1] + bin_edges[1:]) / 2

axes[0].plot([0, 1], [0, 1], 'k--', alpha=0.5, label='Perfect calibration')

axes[0].plot(bin_centers, bin_means, 'bo-', linewidth=2, markersize=8, label='Model predictions')

axes[0].set_xlabel('Predicted Probability', fontsize=12)

axes[0].set_ylabel('Actual Proportion Active', fontsize=12)

axes[0].set_title('Probability Model Calibration', fontsize=14)

axes[0].legend()

axes[0].grid(alpha=0.3)

# Revenue prediction accuracy

axes[1].scatter(

in_sample[in_sample['active_2015']==1]['amount_predicted'],

in_sample[in_sample['active_2015']==1]['revenue_2015'],

alpha=0.3,

edgecolors='b',

facecolors='none'

)

axes[1].plot([0, 500], [0, 500], 'r--', alpha=0.5, label='Perfect prediction')

axes[1].set_xlabel('Predicted Revenue ($)', fontsize=12)

axes[1].set_ylabel('Actual Revenue ($)', fontsize=12)

axes[1].set_title('Revenue Prediction Accuracy', fontsize=14)

axes[1].set_xlim(0, 500)

axes[1].set_ylim(0, 500)

axes[1].legend()

axes[1].grid(alpha=0.3)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.savefig('model_calibration.png', dpi=150, bbox_inches='tight')

plt.show()

When we predict 30% probability, about 30% of those customers actually purchase. When we predict 80%, about 80% purchase.

Applying Models to 2016 Predictions

With validated models in hand, we can now make predictions for 2016.

# Calculate current RFM (as of end of 2015, predicting 2016)

customers_current = calculate_rfm(df)

# Generate 2016 predictions

customers_current['prob_predicted'] = prob_model_fit.predict(customers_current)

customers_current['log_amount_predicted'] = amount_model_v2_fit.predict(customers_current)

customers_current['amount_predicted'] = np.exp(customers_current['log_amount_predicted'])

customers_current['score_predicted'] = (

customers_current['prob_predicted'] * customers_current['amount_predicted']

)

print("\n2016 Prediction Summary:")

print(f"Total customers: {len(customers_current)}")

print(f"Average predicted probability: {customers_current['prob_predicted'].mean():.2%}")

print(f"Average predicted spend (if active): ${customers_current['amount_predicted'].mean():.2f}")

print(f"Average expected value per customer: ${customers_current['score_predicted'].mean():.2f}")

print(f"\nExpected total 2016 revenue: ${customers_current['score_predicted'].sum():,.2f}")

2016 Prediction Summary:

Total customers: 18417

Average predicted probability: 22.00%

Average predicted spend (if active): $65.63

Average expected value per customer: $18.83

Expected total 2016 revenue: $346,822.11

Our model predicts roughly $347,000 in 2016 revenue from existing customers. This becomes a baseline for business planning.

Identifying High-Value Target Customers

The real business value comes from using these predictions to guide marketing investment. Let’s identify our top targets:

# Segment customers by predicted value

customers_current['value_tier'] = pd.cut(

customers_current['score_predicted'],

bins=[0, 10, 30, 50, 100, float('inf')],

labels=['Very Low (<$10)', 'Low ($10-30)', 'Medium ($30-50)',

'High ($50-100)', 'Very High (>$100)']

)

tier_summary = customers_current.groupby('value_tier', observed=True).agg({

'customer_id': 'count',

'score_predicted': 'sum',

'prob_predicted': 'mean',

'amount_predicted': 'mean'

}).rename(columns={'customer_id': 'n_customers'})

tier_summary['pct_customers'] = tier_summary['n_customers'] / len(customers_current) * 100

tier_summary['pct_revenue'] = tier_summary['score_predicted'] / tier_summary['score_predicted'].sum() * 100

print("\nCustomer Value Tiers:")

print(tabulate(tier_summary.round(2), headers='keys', tablefmt='psql'))

Customer Value Tiers:

+----------------------+--------------+------------------+------------------+-------------------+-----------------+---------------+

| value_tier | n_customers | score_predicted | prob_predicted | amount_predicted | pct_customers | pct_revenue |

+----------------------+--------------+------------------+------------------+-------------------+-----------------+---------------+

| Very Low (<$10) | 10831.00 | 17843.35 | 0.07 | 43.71 | 58.81 | 5.14 |

| Low ($10-30) | 4177.00 | 78739.87 | 0.28 | 70.61 | 22.68 | 22.70 |

| Medium ($30-50) | 1456.00 | 57494.24 | 0.49 | 79.92 | 7.91 | 16.58 |

| High ($50-100) | 1097.00 | 77287.48 | 0.69 | 100.46 | 5.96 | 22.29 |

| Very High (>$100) | 856.00 | 115457.17 | 0.85 | 159.23 | 4.65 | 33.29 |

+----------------------+--------------+------------------+------------------+-------------------+-----------------+---------------+

The top two tiers (Very High and High) represent just 11% of customers but are predicted to generate 56% of revenue. Let’s identify specific high-value customers:

# Get top 500 customers by predicted score

top_customers = customers_current.nlargest(500, 'score_predicted')

print("\nTop 500 Customer Profile:")

print(f"Average predicted probability: {top_customers['prob_predicted'].mean():.2%}")

print(f"Average predicted spend: ${top_customers['amount_predicted'].mean():.2f}")

print(f"Average expected value: ${top_customers['score_predicted'].mean():.2f}")

print(f"Total expected revenue from top 500: ${top_customers['score_predicted'].sum():,.2f}")

print(f"Percentage of total predicted revenue: {top_customers['score_predicted'].sum() / customers_current['score_predicted'].sum():.1%}")

# Export for CRM system

top_customers[['customer_id', 'score_predicted', 'prob_predicted',

'amount_predicted', 'recency', 'frequency']].to_csv(

'top_500_customers_2016.csv', index=False

)

print("\nTop 500 customers exported to 'top_500_customers_2016.csv'")

Top 500 Customer Profile:

Average predicted probability: 94.00%

Average predicted spend: $212.45

Average expected value: $199.70

Total expected revenue from top 500: $99,848.91

Percentage of total predicted revenue: 28.8%

Top 500 customers exported to 'top_500_customers_2016.csv'

The top 500 customers (2.7% of the database) are predicted to generate nearly 29% of total 2016 revenue. These customers have a 94% probability of purchasing and are expected to spend over $200 each.

Business Applications

Marketing budget: Concentrate resources on the 1,953 customers in High and Very High tiers (11% of the base, 56% of predicted revenue).

Reactivation: Target only inactive customers with high historical value and relatively recent lapse.

Inventory planning: The predicted revenue of $347,000 provides a baseline for purchasing decisions.

Churn risk: Customers with historically high spending but low predicted probability are at risk and worth proactive outreach.

Model Maintenance

Retraining: Customer behavior changes over time. Most businesses retrain quarterly or annually.

Thresholds: Adjust the score thresholds ($10, $30, $50) to reflect your unit economics and margins.

Integration: Build data pipelines that automatically generate updated scores and push them to downstream systems.

What’s Next

These predictions answer “what will customers do next year?” The next tutorial tackles Customer Lifetime Value (CLV): “what is each customer worth over their entire relationship with our company?”

CLV extends our one-year predictions to multi-year horizons using Markov chains. We’ll project how customers migrate between segments over time, translate those projections into revenue streams, and discount back to present value.

Conclusion

Our two-model approach (probability of purchase and amount spent) provides a practical framework that balances statistical rigor with business usability. The models are deliberately simple: five RFM features, logistic regression, and ordinary least squares. Simple models are easier to understand, maintain, debug, and explain.

The business value comes from systematic application. Focus resources on high-probability, high-value customers. Monitor performance against predictions to detect changes. Use the models as decision support tools.

References

-

Lilien, Gary L, Arvind Rangaswamy, and Arnaud De Bruyn. 2017. Principles of Marketing Engineering and Analytics. State College, PA: DecisionPro.

-

Arnaud De Bruyn. Foundations of Marketing Analytics (MOOC). Coursera.

-

Hosmer, David W., Stanley Lemeshow, and Rodney X. Sturdivant. 2013. Applied Logistic Regression. 3rd ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

-

James, Gareth, Daniela Witten, Trevor Hastie, and Robert Tibshirani. 2021. An Introduction to Statistical Learning: With Applications in R. 2nd ed. New York: Springer.

-

Fader, Peter S., and Bruce G. S. Hardie. 2009. “Probability Models for Customer-Base Analysis.” Journal of Interactive Marketing 23 (1): 61-69.

-

Dataset from Github repo. Accessed 15 December 2021.

Data Science