Forecasting Customer Lifetime Value Using RFM-Analysis and Markov Chain

Introduction

Customer Lifetime Value (CLV) quantifies the total present value of all future cash flows from a customer relationship. It transforms customer analytics from describing the past to valuing the future.

In our first tutorial, we segmented customers using hierarchical clustering. The second tutorial implemented managerial segmentation with business rules. Our third tutorial built models that forecast next-period purchase probability and spending.

Today we forecast customer value over multiple years using Markov chain modeling. We’ll capture how customers migrate between segments over time, project future revenue streams, and discount them to present value.

Why CLV Matters

Acquiring new customers costs five to twenty-five times more than retaining existing ones. You can’t treat a customer who will generate $5,000 over five years the same as one who will generate $50. Without CLV, you can’t make these distinctions rationally.

The Business Case

Consider: your acquisition campaign costs $100,000 and brings 500 new customers generating $120,000 in immediate revenue. Looks profitable. But if discount-driven customers generate only $150 in lifetime value while full-price customers generate $800, the campaign might actually destroy value. CLV reveals the true economics.

CLV guides decisions across the business: acquisition channel comparison, optimal acquisition spending, retention investment prioritization, and product development focus.

Markov Chain Migration Models

Our approach uses a migration model based on Markov chains. By comparing customer segments from consecutive years, we see how customers moved between segments. Each transition has a probability we can estimate from historical data. These transition probabilities form a matrix.

Once you have this transition matrix, you can project it forward indefinitely. Multiply today’s distribution by the transition matrix to get next year’s. Keep going to project five or ten years forward.

The key assumption is that the process is memoryless: future transitions depend only on the current segment, not the path that led there. We also assume no new customer acquisition in our projections (we’re valuing the existing customer base only).

Building the Analysis in Python

Let’s implement this framework using our familiar dataset. We’ll reuse the segmentation functions we developed in the previous tutorial to keep our code clean and maintainable.

# Import required libraries

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import squarify

from tabulate import tabulate

# Set up environment

pd.options.display.float_format = '{:,.2f}'.format

plt.rcParams["figure.figsize"] = (12, 8)

# Load the dataset

columns = ['customer_id', 'purchase_amount', 'date_of_purchase']

df = pd.read_csv('purchases.txt', header=None, sep='\t', names=columns)

# Convert to datetime and create time-based features

df['date_of_purchase'] = pd.to_datetime(df['date_of_purchase'], format='%Y-%m-%d')

df['year_of_purchase'] = df['date_of_purchase'].dt.year

# Set reference date for calculating recency

basedate = pd.Timestamp('2016-01-01')

df['days_since'] = (basedate - df['date_of_purchase']).dt.days

Now we’ll use our reusable functions from the previous tutorial to calculate RFM and segment customers:

def calculate_rfm(dataframe, reference_date=None, days_lookback=None):

"""

Calculate RFM metrics for customers.

Parameters:

-----------

dataframe : DataFrame

Transaction data with customer_id, purchase_amount, days_since

days_lookback : int, optional

Only consider transactions within this many days (default: None, uses all)

Returns:

--------

DataFrame with customer_id and RFM metrics

"""

if days_lookback is not None:

df_filtered = dataframe[dataframe['days_since'] > days_lookback].copy()

df_filtered['days_since'] = df_filtered['days_since'] - days_lookback

else:

df_filtered = dataframe.copy()

rfm = df_filtered.groupby('customer_id').agg({

'days_since': ['min', 'max'],

'customer_id': 'count',

'purchase_amount': ['mean', 'max']

})

rfm.columns = ['recency', 'first_purchase', 'frequency', 'avg_amount', 'max_amount']

rfm = rfm.reset_index()

return rfm

def segment_customers(rfm_data):

"""

Segment customers based on RFM metrics using managerial rules.

"""

customers = rfm_data.copy()

conditions = [

customers['recency'] > 365 * 3,

(customers['recency'] <= 365 * 3) & (customers['recency'] > 365 * 2),

(customers['recency'] <= 365 * 2) & (customers['recency'] > 365) &

(customers['first_purchase'] <= 365 * 2),

(customers['recency'] <= 365 * 2) & (customers['recency'] > 365) &

(customers['avg_amount'] >= 100),

(customers['recency'] <= 365 * 2) & (customers['recency'] > 365) &

(customers['avg_amount'] < 100),

(customers['recency'] <= 365) & (customers['first_purchase'] <= 365),

(customers['recency'] <= 365) & (customers['avg_amount'] >= 100),

(customers['recency'] <= 365) & (customers['avg_amount'] < 100)

]

choices = [

'inactive',

'cold',

'new warm',

'warm high value',

'warm low value',

'new active',

'active high value',

'active low value'

]

customers['segment'] = np.select(conditions, choices, default='other')

segment_order = [

'inactive', 'cold', 'warm high value', 'warm low value', 'new warm',

'active high value', 'active low value', 'new active'

]

customers['segment'] = pd.Categorical(

customers['segment'],

categories=segment_order,

ordered=True

)

return customers.sort_values('segment')

# Calculate segments for both years

customers_2014 = calculate_rfm(df, days_lookback=365)

customers_2014 = segment_customers(customers_2014)

customers_2015 = calculate_rfm(df)

customers_2015 = segment_customers(customers_2015)

print("2014 Segment Distribution:")

print(customers_2014['segment'].value_counts())

print("\n2015 Segment Distribution:")

print(customers_2015['segment'].value_counts())

2014 Segment Distribution:

inactive 8602

active low value 3094

cold 1923

new active 1474

new warm 936

warm low value 835

active high value 476

warm high value 108

Name: segment, dtype: int64

2015 Segment Distribution:

inactive 9158

active low value 3313

cold 1903

new active 1512

new warm 938

warm low value 901

active high value 573

warm high value 119

Name: segment, dtype: int64

Inactive customers grew from 8,602 to 9,158 (churn). Active high value grew from 476 to 573 (customer development). Understanding these flows becomes critical for CLV estimation.

Constructing the Transition Matrix

The transition matrix captures the probability of moving from any segment in 2014 to any segment in 2015. To build it, we need to track individual customer movements across both years:

# Merge 2014 and 2015 segments by customer_id

# Use left join to keep all 2014 customers

transitions_df = customers_2014[['customer_id', 'segment']].merge(

customers_2015[['customer_id', 'segment']],

on='customer_id',

how='left',

suffixes=('_2014', '_2015')

)

# Handle customers who didn't appear in 2015 data (extremely rare edge case)

# They would have transitioned to inactive

transitions_df['segment_2015'] = transitions_df['segment_2015'].fillna('inactive')

print("\nSample transitions:")

print(tabulate(transitions_df.tail(10), headers='keys', tablefmt='psql', showindex=False))

Sample transitions:

+---------------+----------------+----------------+

| customer_id | segment_2014 | segment_2015 |

+---------------+----------------+----------------+

| 221470 | new active | new warm |

| 221460 | new active | active low value |

| 221450 | new active | new warm |

| 221430 | new active | new warm |

| 245840 | new active | new warm |

| 245830 | new active | active low value |

| 245820 | new active | active low value |

| 245810 | new active | new warm |

| 245800 | new active | active low value |

| 245790 | new active | new warm |

+---------------+----------------+----------------+

Now we create the transition matrix using cross-tabulation:

# Create cross-tabulation of transitions (raw counts)

transition_counts = pd.crosstab(

transitions_df['segment_2014'],

transitions_df['segment_2015'],

dropna=False

)

print("\nTransition Counts (2014 → 2015):")

print(transition_counts)

Transition Counts (2014 → 2015):

segment_2015 inactive cold warm high value warm low value new warm \

segment_2014

inactive 7227 0 0 0 0

cold 1931 0 0 0 0

warm high value 0 75 0 0 0

warm low value 0 689 0 0 0

new warm 0 1139 0 0 0

active high value 0 0 119 0 0

active low value 0 0 0 901 0

new active 0 0 0 0 938

segment_2015 active high value active low value

segment_2014

inactive 35 250

cold 22 200

warm high value 35 1

warm low value 1 266

new warm 15 96

active high value 354 2

active low value 22 2088

new active 89 410

Of 8,602 inactive customers in 2014, 7,227 remained inactive (84%). Of 476 active high value, 354 stayed in that segment (74%). The new active segment shows 64% became new warm (didn’t repurchase), highlighting the importance of second-purchase campaigns.

Now we convert counts to probabilities:

# Convert counts to probabilities

transition_matrix = transition_counts.div(transition_counts.sum(axis=1), axis=0)

print("\nTransition Matrix (Probabilities):")

print(transition_matrix.round(3))

Transition Matrix (Probabilities):

segment_2015 inactive cold warm high value warm low value new warm \

segment_2014

inactive 0.962 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000

cold 0.897 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000

warm high value 0.000 0.676 0.000 0.000 0.000

warm low value 0.000 0.721 0.000 0.000 0.000

new warm 0.000 0.912 0.000 0.000 0.000

active high value 0.000 0.000 0.251 0.000 0.000

active low value 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.299 0.000

new active 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.645

segment_2015 active high value active low value

segment_2014

inactive 0.005 0.033

cold 0.010 0.093

warm high value 0.315 0.009

warm low value 0.001 0.278

new warm 0.012 0.077

active high value 0.746 0.004

active low value 0.007 0.693

new active 0.061 0.282

An inactive 2014 customer has a 96.2% chance of staying inactive, 0.5% of becoming active high value, and 3.3% of becoming active low value.

Validating the Transition Matrix

Does multiplying our 2014 distribution by the transition matrix accurately reproduce the actual 2015 distribution?

# Get 2014 segment counts as a vector

segment_2014_counts = customers_2014['segment'].value_counts().reindex(

transition_matrix.index, fill_value=0

)

# Predict 2015 distribution by matrix multiplication

predicted_2015 = segment_2014_counts.dot(transition_matrix).round(0)

# Get actual 2015 distribution

actual_2015 = customers_2015['segment'].value_counts().reindex(

transition_matrix.columns, fill_value=0

)

# Compare predictions to actuals

validation = pd.DataFrame({

'2014_actual': segment_2014_counts,

'2015_predicted': predicted_2015.astype(int),

'2015_actual': actual_2015,

'error': actual_2015 - predicted_2015.astype(int),

'pct_error': ((actual_2015 - predicted_2015) / actual_2015 * 100).round(1)

})

print("\nTransition Matrix Validation:")

print(tabulate(validation, headers='keys', tablefmt='psql'))

Transition Matrix Validation:

+-------------------+--------------+------------------+---------------+---------+-------------+

| segment | 2014_actual | 2015_predicted | 2015_actual | error | pct_error |

+-------------------+--------------+------------------+---------------+---------+-------------+

| inactive | 8602.00 | 9212.00 | 9158.00 | -54.00 | -0.60 |

| cold | 1923.00 | 1781.00 | 1903.00 | 122.00 | 6.41 |

| warm high value | 108.00 | 137.00 | 119.00 | -18.00 | -15.13 |

| warm low value | 835.00 | 931.00 | 901.00 | -30.00 | -3.33 |

| new warm | 936.00 | 0.00 | 938.00 | 938.00 | 100.00 |

| active high value | 476.00 | 552.00 | 573.00 | 21.00 | 3.67 |

| active low value | 3094.00 | 3292.00 | 3313.00 | 21.00 | 0.63 |

| new active | 1474.00 | 0.00 | 1512.00 | 1512.00 | 100.00 |

+-------------------+--------------+------------------+---------------+---------+-------------+

Most segments have errors under 7%. Inactive customers predicted at 9,212 vs. actual 9,158 (0.6% error). The new warm and new active segments show 100% error because “new” customers can only enter through acquisition, which our transition matrix doesn’t model.

Projecting Future Segment Evolution

With a validated transition matrix, we can now project customer distribution across future years. We’ll create a matrix where rows represent segments and columns represent years from 2015 through 2025:

# Initialize projection matrix

# Rows = segments, Columns = years

years = np.arange(2015, 2026)

segment_projection = pd.DataFrame(

0,

index=customers_2015['segment'].cat.categories,

columns=years

)

# Populate 2015 with actual counts

segment_projection[2015] = customers_2015['segment'].value_counts().reindex(

segment_projection.index, fill_value=0

)

# Project forward using matrix multiplication

for year in range(2016, 2026):

segment_projection[year] = segment_projection[year-1].dot(transition_matrix).round(0)

# Convert to integers (can't have fractional customers)

segment_projection = segment_projection.astype(int)

print("\nSegment Projection (2015-2025):")

print(segment_projection)

Segment Projection (2015-2025):

2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022 2023 2024 2025

inactive 9158 10517 11539 12266 12940 13185 13386 13542 13664 13760 13834

cold 1903 1584 1711 1674 1621 1582 1540 1509 1685 1665 1651

warm high value 119 144 165 160 157 152 149 146 143 141 139

warm low value 901 991 1058 989 938 884 844 813 789 771 756

new warm 938 987 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

active high value 573 657 639 625 608 594 582 571 562 554 548

active low value 3313 3537 3306 3134 2954 2820 2717 2637 2575 2527 2490

new active 1512 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

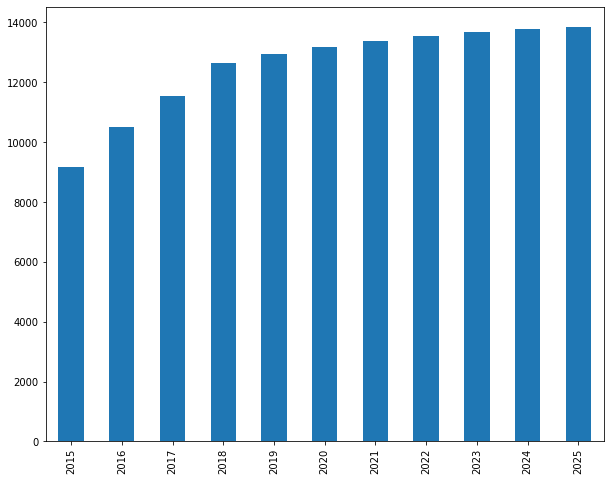

Inactive customers grow from 9,158 (2015) to 13,834 (2025). Active low value decline from 3,313 to 2,490. This baseline projection shows the natural erosion rate without acquisition or retention initiatives.

Let’s visualize inactive customer growth:

# Plot inactive customer trajectory

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(12, 6))

segment_projection.loc['inactive'].plot(kind='bar', ax=ax, color='#9b59b6', alpha=0.7)

ax.set_xlabel('Year', fontsize=12)

ax.set_ylabel('Number of Customers', fontsize=12)

ax.set_title('Projected Inactive Customer Growth (No New Acquisition)', fontsize=14)

ax.grid(axis='y', alpha=0.3)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.savefig('inactive_projection.png', dpi=150, bbox_inches='tight')

plt.show()

Without intervention, inactive customers grow by 51% over ten years.

Computing Revenue Projections

We need the average revenue generated by each segment:

# Calculate average 2015 revenue by segment

revenue_2015 = df[df['year_of_purchase'] == 2015].groupby('customer_id')['purchase_amount'].sum()

customers_with_revenue = customers_2015.merge(

revenue_2015.rename('revenue_2015'),

on='customer_id',

how='left'

)

customers_with_revenue['revenue_2015'] = customers_with_revenue['revenue_2015'].fillna(0)

segment_revenue = customers_with_revenue.groupby('segment', observed=True)['revenue_2015'].mean()

print("\nAverage 2015 Revenue by Segment:")

print(segment_revenue.round(2))

Average 2015 Revenue by Segment:

segment

inactive 0.00

cold 0.00

warm high value 0.00

warm low value 0.00

new warm 0.00

active high value 323.57

active low value 52.31

new active 79.17

Name: revenue_2015, dtype: float64

Active high value average $324/year. Active low value average $52. Losing 100 active high value customers costs $32,357 in annual revenue vs. only $5,231 for active low value. Now we project revenue:

# Create revenue vector (aligned with segment order in our projection matrix)

revenue_vector = segment_revenue.reindex(segment_projection.index, fill_value=0)

# Calculate revenue projection for each year

revenue_projection = segment_projection.multiply(revenue_vector, axis=0)

# Sum across segments to get total yearly revenue

yearly_revenue = revenue_projection.sum(axis=0)

print("\nProjected Yearly Revenue (2015-2025):")

print(yearly_revenue.round(0))

Projected Yearly Revenue (2015-2025):

2015 478414.00

2016 397606.00

2017 379698.00

2018 366171.00

2019 351254.00

2020 339715.00

2021 330444.00

2022 322700.00

2023 316545.00

2024 311445.00

2025 307568.00

dtype: float64

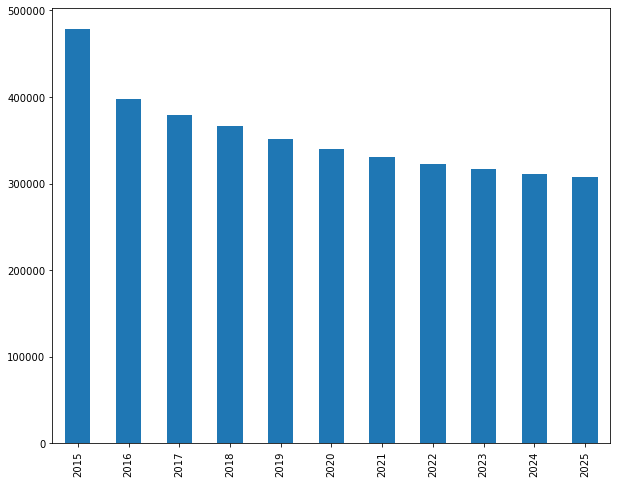

Revenue declines from $478,414 (2015) to $307,568 (2025), a 36% drop. Let’s visualize:

# Plot revenue projection

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(12, 6))

yearly_revenue.plot(kind='bar', ax=ax, color='#3498db', alpha=0.7)

ax.set_xlabel('Year', fontsize=12)

ax.set_ylabel('Revenue ($)', fontsize=12)

ax.set_title('Projected Annual Revenue (No Acquisition, No Discounting)', fontsize=14)

ax.yaxis.set_major_formatter(plt.FuncFormatter(lambda x, p: f'${x/1000:.0f}K'))

ax.grid(axis='y', alpha=0.3)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.savefig('revenue_projection.png', dpi=150, bbox_inches='tight')

plt.show()

Without acquisition and retention initiatives, revenue decays by over a third.

Calculating Customer Lifetime Value with Discounting

A dollar received ten years from now is worth less than a dollar today. Discounting adjusts future cash flows to present value:

\[PV = \frac{FV}{(1 + r)^t}\]Where PV is present value, FV is future value, r is the discount rate, and t is time in years. The discount rate typically reflects your cost of capital (what you pay to borrow money) or your opportunity cost (what you could earn investing elsewhere). We’ll use 10% as a reasonable discount rate for a retail business.

# Set discount rate and calculate discount factors

discount_rate = 0.10

discount_factors = 1 / ((1 + discount_rate) ** np.arange(0, 11))

print("\nDiscount Factors (10% rate):")

discount_df = pd.DataFrame({

'year': years,

'discount_factor': discount_factors,

'dollar_value': discount_factors

}).round(3)

print(tabulate(discount_df, headers='keys', tablefmt='psql', showindex=False))

Discount Factors (10% rate):

+--------+-------------------+----------------+

| year | discount_factor | dollar_value |

+--------+-------------------+----------------+

| 2015 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| 2016 | 0.909 | 0.909 |

| 2017 | 0.826 | 0.826 |

| 2018 | 0.751 | 0.751 |

| 2019 | 0.683 | 0.683 |

| 2020 | 0.621 | 0.621 |

| 2021 | 0.564 | 0.564 |

| 2022 | 0.513 | 0.513 |

| 2023 | 0.467 | 0.467 |

| 2024 | 0.424 | 0.424 |

| 2025 | 0.386 | 0.386 |

+--------+-------------------+----------------+

By 2025 (ten years out), each dollar is worth just $0.39. Now we apply discount factors to revenue:

# Calculate discounted yearly revenue

discounted_revenue = yearly_revenue * discount_factors

print("\nRevenue Comparison (Nominal vs. Present Value):")

comparison = pd.DataFrame({

'year': years,

'nominal_revenue': yearly_revenue,

'discount_factor': discount_factors,

'present_value': discounted_revenue

}).round(0)

print(tabulate(comparison, headers='keys', tablefmt='psql', showindex=False))

Revenue Comparison (Nominal vs. Present Value):

+--------+-------------------+-------------------+----------------+

| year | nominal_revenue | discount_factor | present_value |

+--------+-------------------+-------------------+-----------------|

| 2015 | 478414.00 | 1.00 | 478414.00 |

| 2016 | 397606.00 | 0.91 | 361460.00 |

| 2017 | 379698.00 | 0.83 | 313800.00 |

| 2018 | 366171.00 | 0.75 | 275110.00 |

| 2019 | 351254.00 | 0.68 | 239911.00 |

| 2020 | 339715.00 | 0.62 | 210936.00 |

| 2021 | 330444.00 | 0.56 | 186527.00 |

| 2022 | 322700.00 | 0.51 | 165596.00 |

| 2023 | 316545.00 | 0.47 | 147671.00 |

| 2024 | 311445.00 | 0.42 | 132083.00 |

| 2025 | 307568.00 | 0.39 | 118581.00 |

+--------+-------------------+-------------------+-----------------|

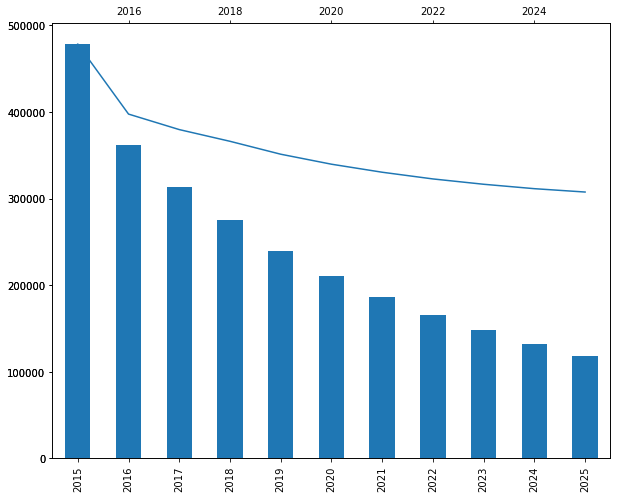

The $307,568 in 2025 nominal revenue is worth only $118,581 in present value. Let’s visualize:

# Plot nominal vs. discounted revenue

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(12, 6))

x = np.arange(len(years))

width = 0.35

bars1 = ax.bar(x - width/2, yearly_revenue, width, label='Nominal Revenue',

color='#3498db', alpha=0.7)

bars2 = ax.bar(x + width/2, discounted_revenue, width, label='Present Value',

color='#e74c3c', alpha=0.7)

ax.set_xlabel('Year', fontsize=12)

ax.set_ylabel('Revenue ($)', fontsize=12)

ax.set_title('Nominal vs. Discounted Revenue Projections', fontsize=14)

ax.set_xticks(x)

ax.set_xticklabels(years)

ax.yaxis.set_major_formatter(plt.FuncFormatter(lambda x, p: f'${x/1000:.0f}K'))

ax.legend()

ax.grid(axis='y', alpha=0.3)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.savefig('revenue_discounted_comparison.png', dpi=150, bbox_inches='tight')

plt.show()

Computing Total Customer Lifetime Value

CLV is the sum of all discounted future cash flows:

# Calculate cumulative metrics

cumulative_nominal = yearly_revenue.cumsum()

cumulative_pv = discounted_revenue.cumsum()

# Calculate total CLV (sum of all discounted cash flows)

total_clv = discounted_revenue.sum()

total_customers = len(customers_2015)

clv_per_customer = total_clv / total_customers

print(f"\nCustomer Lifetime Value Analysis:")

print(f"Total customer base (2015): {total_customers:,}")

print(f"Total CLV (10-year, discounted): ${total_clv:,.2f}")

print(f"Average CLV per customer: ${clv_per_customer:,.2f}")

print(f"\nComparison:")

print(f"Total nominal revenue (10-year): ${yearly_revenue.sum():,.2f}")

print(f"Discount impact: {(1 - total_clv/yearly_revenue.sum())*100:.1f}% reduction")

Customer Lifetime Value Analysis:

Total customer base (2015): 18,417

Total CLV (10-year, discounted): $2,630,089.00

Average CLV per customer: $142.80

Comparison:

Total nominal revenue (10-year): $3,661,560.00

Discount impact: 28.2% reduction

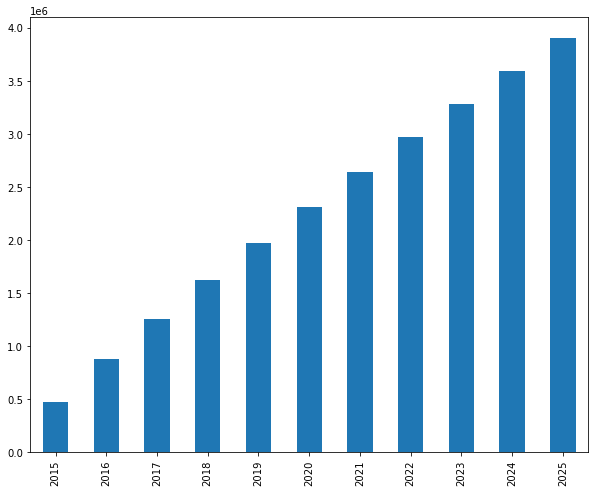

Total CLV is $2.63 million across 18,417 customers, or $142.80 per customer average. If you want a 5:1 CLV to CAC ratio, spend no more than $29 to acquire a typical customer. Let’s visualize cumulative value:

# Plot cumulative CLV over time

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(12, 6))

ax.plot(years, cumulative_pv/1000, marker='o', linewidth=2.5,

markersize=8, color='#2ecc71', label='Cumulative CLV (Present Value)')

ax.fill_between(years, 0, cumulative_pv/1000, alpha=0.2, color='#2ecc71')

ax.set_xlabel('Year', fontsize=12)

ax.set_ylabel('Cumulative Value ($K)', fontsize=12)

ax.set_title('Cumulative Customer Lifetime Value (10-year, Discounted)', fontsize=14)

ax.grid(alpha=0.3)

ax.legend(fontsize=11)

# Add annotation for total CLV

ax.annotate(f'Total CLV: ${total_clv/1000:.0f}K',

xy=(2025, cumulative_pv.iloc[-1]/1000),

xytext=(2022, cumulative_pv.iloc[-1]/1000 + 200),

fontsize=11,

bbox=dict(boxstyle='round', facecolor='wheat', alpha=0.5),

arrowprops=dict(arrowstyle='->', connectionstyle='arc3,rad=0.3'))

plt.tight_layout()

plt.savefig('cumulative_clv.png', dpi=150, bbox_inches='tight')

plt.show()

Most customer value is realized early in the relationship. The first three years generate $1.33 million (51% of total CLV). The last three years generate only $498K (19%).

Segment-Specific Lifetime Values

How much is an active high value customer worth versus an active low value customer?

# Calculate segment-specific CLV

segment_clv = revenue_projection.multiply(discount_factors, axis=1).sum(axis=1) / segment_projection[2015]

segment_clv = segment_clv.replace([np.inf, -np.inf], 0) # Handle divide by zero

# Create comprehensive segment analysis

segment_analysis = pd.DataFrame({

'2015_count': segment_projection[2015],

'avg_2015_revenue': revenue_vector,

'total_segment_clv': revenue_projection.multiply(discount_factors, axis=1).sum(axis=1),

'clv_per_customer': segment_clv

}).round(2)

segment_analysis['pct_of_total_clv'] = (

segment_analysis['total_segment_clv'] / segment_analysis['total_segment_clv'].sum() * 100

).round(1)

print("\nSegment-Level CLV Analysis:")

print(tabulate(segment_analysis, headers='keys', tablefmt='psql'))

Segment-Level CLV Analysis:

+-------------------+--------------+---------------------+---------------------+---------------------+---------------------+

| segment | 2015_count | avg_2015_revenue | total_segment_clv | clv_per_customer | pct_of_total_clv |

+-------------------+--------------+---------------------+---------------------+---------------------+---------------------+

| inactive | 9158.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.0 |

| cold | 1903.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.0 |

| warm high value | 119.00 | 0.00 | 43842.90 | 368.43 | 1.7 |

| warm low value | 901.00 | 0.00 | 40766.61 | 45.25 | 1.5 |

| new warm | 938.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.0 |

| active high value | 573.00 | 323.57 | 1800952.04 | 3143.55 | 68.5 |

| active low value | 3313.00 | 52.31 | 675964.03 | 204.02 | 25.7 |

| new active | 1512.00 | 79.17 | 68563.39 | 45.34 | 2.6 |

+-------------------+--------------+---------------------+---------------------+---------------------+---------------------+

Active high value customers average $3,144 in lifetime value. Active low value average $204. The ratio is 15:1. The 573 active high value customers (3% of the base) generate 68.5% of total value.

Implications: Losing an active high value customer forfeits $3,144. You can justify spending hundreds on personalized retention. Losing an active low value customer forfeits $204, suggesting automated retention. Acquisition targeting should focus on prospects likely to become high-value.

Business Applications

Acquisition evaluation: Strategy A acquires 1,000 discount customers at $150 each (CLV: $204). Strategy B acquires 300 premium customers at $200 each (CLV: $3,144). Strategy A net value: $54,000. Strategy B net value: $883,200. Fewer high-value customers beat many low-value customers.

Retention investment: Improving high-value retention by 10% saves 57 customers × $3,144 = $179,208. Same improvement for low-value saves 331 customers × $204 = $67,524. Focus retention on high-value first.

Product decisions: A premium product line costing $500,000 might increase high-value customer spending by 23%, generating ~$350,000 in incremental CLV (present value). Negative NPV unless it attracts additional high-value customers.

Model Limitations

Key assumptions: Stationary transition probabilities (may not hold over 10 years), no customer acquisition modeled, segment-based averaging (ignores within-segment variation), 10% discount rate (sensitivity analysis recommended).

Despite limitations, even a rough CLV estimate beats no estimate. The goal is directing resources toward high-value customers.

Conclusion

The average customer is worth $143 in present value over ten years. But active high value customers are worth $3,144 each, active low value customers $204. The 15:1 ratio means customer selection and retention have enormous financial leverage.

We used simple approaches: logistic regression, OLS, RFM segmentation, transition matrices. These workhorse methods produce interpretable results and integrate into operational systems.

Customer analytics is valuable only when it changes decisions. Start simple. Segment customers. Calculate segment-level revenue. Build transition matrices. Estimate CLV roughly. Guide a few decisions. Measure results. Iterate.

References

-

Lilien, Gary L, Arvind Rangaswamy, and Arnaud De Bruyn. 2017. Principles of Marketing Engineering and Analytics. State College, PA: DecisionPro.

-

Fader, Peter S., and Bruce G. S. Hardie. 2009. “Probability Models for Customer-Base Analysis.” Journal of Interactive Marketing 23 (1): 61-69.

-

Pfeifer, Phillip E., and Robert L. Carraway. 2000. “Modeling Customer Relationships as Markov Chains.” Journal of Interactive Marketing 14 (2): 43-55.

-

Netzer, Oded, and James M. Lattin. 2008. “A Hidden Markov Model of Customer Relationship Dynamics.” Marketing Science 27 (2): 185-204.

-

Grönroos, Christian. 1991. “The Marketing Strategy Continuum: Towards a Marketing Concept for the 1990s.” Management Decision 29 (1). https://doi.org/10.1108/00251749110139106.

-

Gupta, Sunil, Donald R. Lehmann, and Jennifer Ames Stuart. 2004. “Valuing Customers.” Journal of Marketing Research 41 (1): 7-18.

-

Arnaud De Bruyn. Foundations of Marketing Analytics (MOOC). Coursera.

-

Dataset from Github repo. Accessed 15 December 2021.

Data Science