A Billionaire Wore Your History as a Joke. Now What?

Did you feel something when you saw Mark Zuckerberg wearing that shirt? The one with the Latin line: Carthago delenda est. Carthage must be destroyed.

Maybe you laughed. Maybe you rolled your eyes. Maybe you felt a small, irrational irritation, like someone stepped on your foot and then acted surprised you noticed.

If you felt it, good. Carthage is still alive in you. A slogan like that only lands if the target still means something. Otherwise it is just dead Latin on cotton.

And no, I am not claiming that reviving a name revives a civilization. Names do not repair schools or ports. They do not produce research, discipline, or competence. Still, it is hard to pretend symbols do not matter. They influence what a country remembers, what it sidelines, and what it feels comfortable taking pride in. And even if the only measurable effect were to annoy Zuckerberg and his kind, that would still be reason enough to do it.

At this point, you might think that renaming is absurd, complicated, or unserious. That sounds sensible until you look at any map with a bit of historical memory. Leningrad became St. Petersburg again by referendum, despite the emotional weight of the siege. Oslo carried a king’s name for three centuries before Norway restored its medieval name. Jakarta was Batavia under Dutch rule; Indonesia brought back the older name the moment it gained independence. Names are not natural facts. They are choices that harden into habit.

So the question is not whether it can be done. It can. The question is what kind of change avoids creating a new erasure in the process.

The most obvious proposal is also the bluntest: rename the capital. Replace “Tunis” with “Carthage.”

That would solve one problem by creating another. Tunis is not an empty label waiting for a better brand. It is a living city with layers that still breathe: the Medina, the Kasbah, the ville nouvelle, and the long centuries of craft, trade, prayer, and daily life that shaped them. Renaming all of it “Carthage” would not restore history. It would flatten it. It would erase 1,300 years to avenge 2,000, mimicking Rome with different emotions.

A softer version of the same impulse is the compromise people reach for instinctively: rename only the wealthy northern suburbs as Carthage and keep the rest as Tunis. But that risks turning Carthage into a luxury brand, a coastal label for the comfortable. Geography becomes status. The name becomes a badge. That is not historical justice, it is class division with a heroic accent.

And then there is the option that looks like neutrality: do nothing. Let Tunis keep expanding until the word “Tunis” means everything and therefore means nothing. In practice, that is already happening. The metropolitan area stretches, absorbs, and blurs. Meanwhile Carthage remains boxed in behind fences as “the ruins,” a museum label rather than a living part of the city’s identity. Over time, both names lose clarity. One becomes too large to mean anything, and the other becomes too small to belong to anyone.

So what if the problem is not the names themselves, but the way the map is organized?

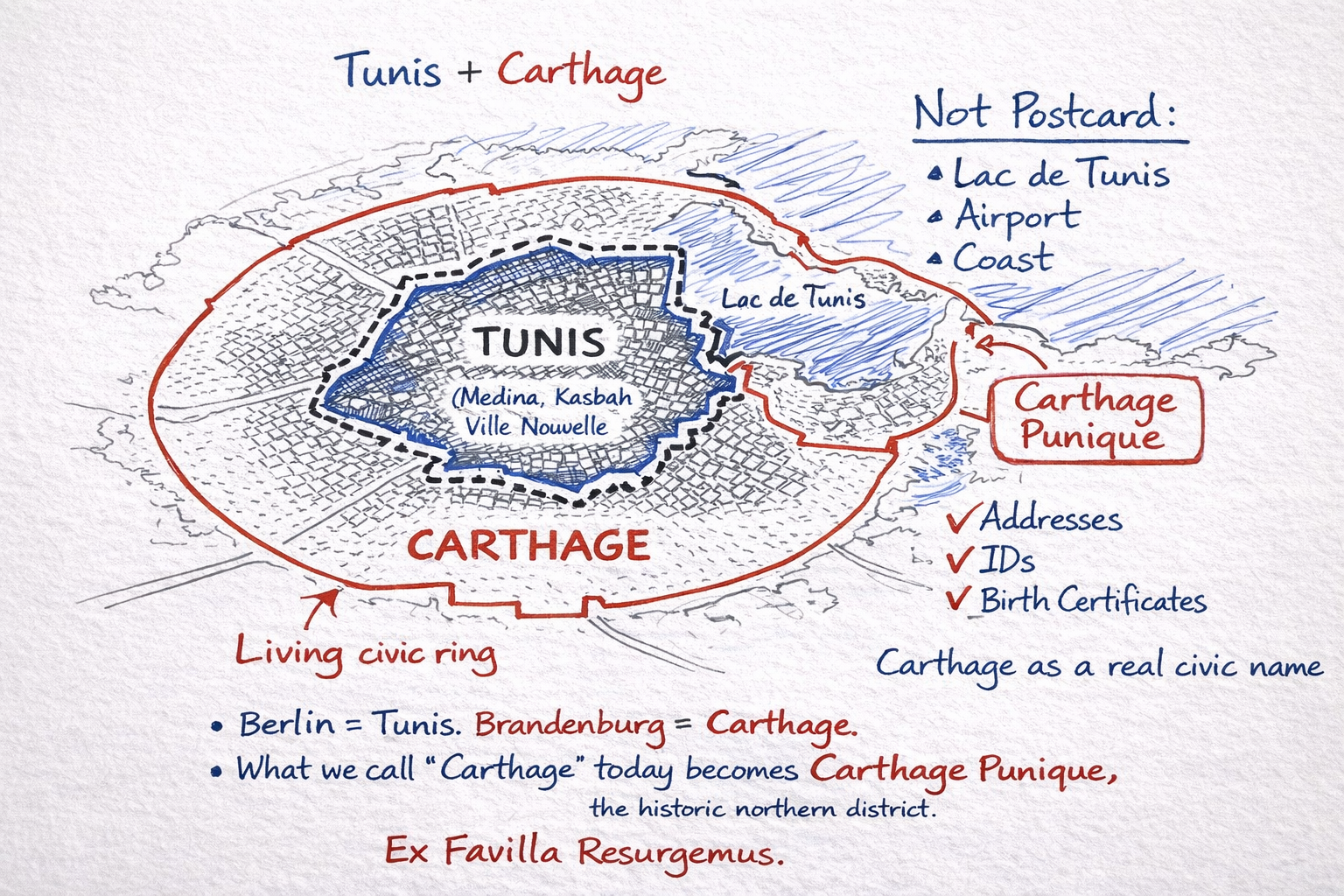

There is a model that helps. Berlin is a city-state inside Brandenburg. Brussels governs itself while sitting inside Flanders. Many capitals function as distinct cores surrounded by a larger region for a simple reason: capitals tend to expand until they devour everything around them, and their names stop referring to anything specific. The “donut” structure draws a line. The core stays legible. The ring stays legible. Both keep their identities, and the map stays honest.

A similar approach could work here. Instead of treating “Tunis” as a blob that expands endlessly, give it a defined shape. Draw a clear boundary around the historic core, the Medina, the Kasbah, the colonial downtown. Make “Tunis” mean something precise again: a protected civic center with legal limits, rather than an accident of sprawl.

Then name the surrounding metropolitan ring Carthage. Not the ruins and not the postcard. Carthage as a living civic space that includes the lake, the coast, the airport, and the neighborhoods already built on that ground. In that arrangement, Tunis stays Tunis. Carthage returns as a name used for ordinary life, not only for archaeology.

This is where the current contradiction becomes impossible to ignore. We already use “Carthage” whenever we want prestige. Our national athletes are the Eagles of Carthage. The presidential palace sits in Carthage. The name already belongs to excellence, victory, and the moments we are proud to broadcast. So Carthage is not taboo. It is already official when it looks good on a jersey or on a headline.

Why, then, does it become “complicated” the moment ordinary people want to claim it as part of everyday belonging? Why should the pre-Islamic layer be tolerated mainly as decoration, ruins for tourists, branding for institutions, symbols for ceremonies, while everyone else is nudged toward a narrower, safer pride?

Once Carthage is real on the map, it becomes real on paper too: addresses, IDs, birth certificates. People will be born in Carthage. The name stops being something you visit behind fences and becomes something you live with, an ordinary civic fact.

So it is worth asking why Carthage should remain confined to an archaeological park and a Latin curse worn on a billionaire’s chest, when Rome and Athens still exist as living cities, and a well-designed map could return Carthage to daily life through a simple administrative adjustment.

Ex Favilla Nos Resurgemus.

Tunisia Colonialism